Journal of Gynecological Research and Obstetrics

Breast cancer metastasis to endometrium: Case report and up-date of literature

1Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Public Hospital of Lodi, via Savoia 1, 26900-Lodi, Italy

2Department of Medical Oncology, Public Hospital of Lodi, via Savoia 1, 26900-Lodi, Italy

3Department of Pathology, Public Hospital of Lodi, via Savoia 1, 26900-Lodi, Italy

4Department of Surgery, Surgical Service of Breast Unit, via Savoia 1, 26900-Lodi, Italy

Author and article information

Cite this as

Garuti G, Sagrada PF, Mirra M, Marrazzo E, Migliaccio S, et al. (2023) Breast cancer metastasis to endometrium: Case report and up-date of literature. J Gynecol Res Obstet. 2023; 9(2): 020-028. Available from: 10.17352/jgro.000121

Copyright License

© 2023 Garuti G, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.Introduction: Breast cancer is the leading neoplasia metastasizing to genital organs. Uterine metastases are seldom reported and those limited to endometrium account for 3.8% of patients with uterine spread. We reported on a woman with breast cancer metastasizing to endometrium and up-date of literature.

Presentation of case: In July 2022, a 59 years-old woman with breast cancer was referred to Gynecological consultation due to Positron Emission Tomography showing an enhanced signal to the endometrium. Throughout the four previous years, she underwent bilateral surgery due to metachronous lobular cancers and adjuvant therapies consisting of Letrozole, Exemestane, chemotherapy, and Tamoxifen. In May 2022, bony metastases were found and she shifted to Abemaciclib/Fulvestrant therapy. No gynecological complaints were recorded, and physical examination was uneventful while Transvaginal Ultrasound demonstrated an enhanced endometrial thickness as a unique abnormality. Hysteroscopy showed mucosal thickenings attributed to Tamoxifen-related cysts formation. The biopsy pathology reported stromal infiltration of neoplastic cells staining for Cytokeratins and GATA-3. Negative staining was reported for PAX-8 and CD-10. On these findings, a breast cancer metastasis was established. Four months later the patients died from metastatic brain progression.

Discussion: Endometrial metastasis from breast cancer is anecdotal. The case described supports that uterine spread is a late event, often concurrent with extragenital metastases and mostly associated with lobular histology. A hysteroscopic view can be misleading and a careful pathological study is needed for a differential diagnosis against endometrial primitiveness.

Conclusion: Endometrial abnormalities in breast cancer patients might be caused by metastasis. The management of these patients is challenging and must be tailored to the clinical background.

Breast cancer is the leading cause of neoplastic-related death and its metastatic progression, mainly found in the lung, bone, liver, or brain, is associated with fatal outcomes [1]. Metastases to genital organs are seldom reported, showing a higher prevalence for ovarian seedings. Isolated uterine metastases from extragenital neoplasia are detected in about 4% of women with cancer spreading to the gynecological tract and breast cancer represents the primitiveness in more than 50% of cases. Among patients showing uterine metastases limited to the uterus, a prevalence of myometrial and endo-myometrial localizations was found in more than 95% of patients, whereas isolated metastases to the endometrium are estimated to occur only in 3.8% of them [2,3]. Uterine spread from breast cancer is often associated with concurrent multi-organ disease progression and early fatal prognosis although in some cases the uterus was found to be the unique localization of recurrence, allowing hysterectomy as an option to control the progression of disease [4-6]. Due to poorly understood biological pathways, lobular breast cancer shows a greater propensity for genital organ spread with respect to the commonest ductal histological type [7]. Abnormal Uterine Bleeding (AUB) is the leading symptom of endometrial pathology. In breast cancer patients, sharing the same genetic and environmental risk factors of endometrial cancer and mainly in those taking Tamoxifen, AUB needs a quick gynecological investigation based on physical examination, cervical cytology, and Transvaginal Ultrasonography (TVU), firstly to exclude a metachronous malignancy arising from the genital tract [8,9]. Hysteroscopy with targeted biopsy represents the reference diagnostics of endometrial pathologies, including endometrial cancer [10,11]. Herein, we describe the gynecological and pathological diagnostic workup carried out in an asymptomatic woman with lobular breast cancer showing an endometrial spread concurrent with bony metastases. Moreover, we reviewed the recent literature relevant to endometrial breast cancer metastases.

Case report

This report was conceptualized in line with the principles of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its amendments. Given the retrospective and observational nature of a clinical case managed by procedures performed as part of routine care, Ethical approval was waived by the local Ethics Committee. The signed consent to publish sensible clinical data was obtained from the husband of the patient, after her death.

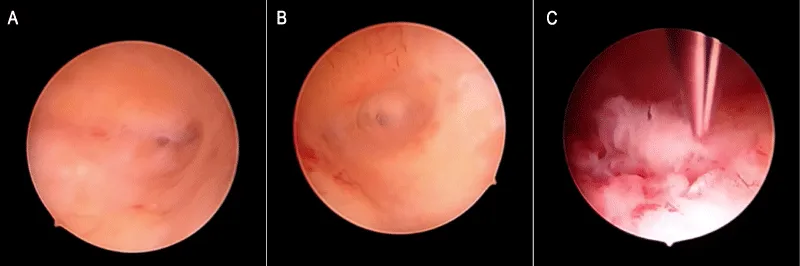

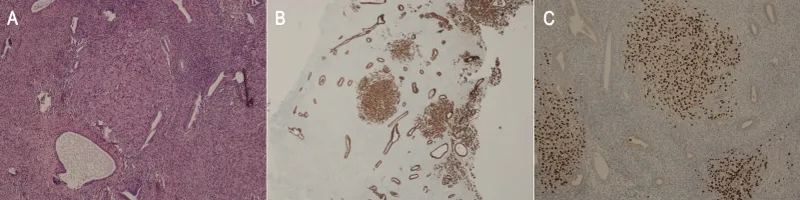

In May 2018, a 55 years-old menopausal woman (Gravida 3, Parous 2, 1 cesarean delivery) without concurrent morbidities, underwent a left breast lumpectomy with sentinel node sampling due to infiltrating breast cancer. Histology reported a grade 2 lobular carcinoma measuring 11 mm with metastasis detected in the sampled lymph node (pN1a). Histochemistry showed 95% expression of both estrogen and progesterone receptors, a ki-67 fraction of 13%, and an absence of c-Erb-B2 reactivity. Radiation therapy was delivered to the residual breast and an adjuvant hormone therapy with Letrozole was started. Before its beginning, gynecological examination and TVU showed normal findings, with an endometrial thickness measuring 3.5 mm. In June 2019, she underwent radical left axillary dissection following the diagnosis of axillary metastases, confirmed in 5 out of 30 removed lymph nodes. A 40% estrogen and 0% progesterone receptors expression, an 18% ki-67 fraction, and a weak positivity for c-Erb-B2 were found. A left supraclavicular radiotherapy was performed and the patient shifted to a therapy with Exemestane. In July 2021, a right metachronous grade 3 lobular breast cancer measuring 9 mm was diagnosed, leading to lumpectomy and sentinel node mapping. The biological profile showed 90% estrogen and 0% progesterone receptors expression, a ki-67 fraction of 25%, and an unexpressed c-Erb-B2. Four removed axillary lymph nodes were negative. Radiotherapy to the residual breast was administered and adjuvant chemotherapy based on 4 cycles of Epirubicin-Cyclophosphamide was started in August 2021, followed by Tamoxifen. In May 2022, we observed a rise in CEA (16 ng/ml), CA 15.3 (77 mUI/ml), and CA 125 (1168 mUI/ml). Computed Tomography showed sacral and lumbar bony metastases. In July 2022, a Positron Emission Tomography (PET) confirmed the lumbo-sacral vertebral body metastases as the only site of recurrence, reporting a weakly enhanced Standardized Uptake Value of 4.6 within the uterine cavity. Based on these findings, the patient stopped Tamoxifen and started Abemaciclib/Fulvestrant administration. A gynecological consultation found normal physical examination in a patient without uterine bleeding complaints. TVU showed a non-homogeneous endometrial thickening, measuring 12 mm on the longitudinal uterine scan with a well-defined endometrial-myometrial junction. No other uterine or ovarian abnormalities were found during ultrasound assessment and a diagnostic hysteroscopy was scheduled. In September 2022, the woman underwent an inpatient video-recorded hysteroscopic diagnostic procedure with a 5 mm operative hysteroscope, using saline as the distending medium. We found a normal lining of endocervical mucosa and a normally structured endometrial cavity. Slight focal and smooth mucosal thickenings sometime showing associated cyst-glands were observed in the background suggesting a sub-atrophic picture, referred to as Tamoxifen-induced stimulation. Neither atypical mucosal overgrowth, neo-angiogenetic vascular network, or necrotic features were found and no suspicion of neoplasia was reported. Using 5Fr mechanical instrumentation we fashioned and retrieved an endometrial biopsy to the posterior uterine wall, targeted to an uneventful mucosal thickening (Figure 1). Histologic assessment by Hematoxylin-Eosin (H&E) staining reported endometrial tissue harboring stromal infiltration by a carcinoma consistent with breast cancer primitiveness. Immunohistochemistry showed positivity for the Cytokeratin Pool (AE1/AE3) and GATA 3 and negative staining for PAX-8 and CD10. Estrogen and progesterone receptors were expressed 10% and 0% while a faint reactivity for c-Erb-B2 was found (Figure 2). Based on these results we confirmed a diagnosis of lobular breast cancer metastatic to endometrium. After the medical oncology joint meeting no gynecological measure was adopted following the diagnosis and the patient continued medical therapy. In November 2022, neurologic symptoms led to the diagnosis of leptomeningeal metastases and the patient died due to the progression of the disease in January 2023.

Discussion

We described the case of an asymptomatic woman with metastatic breast cancer spreading to endometrium through a plausible hematogenous route, based on imaging findings suggesting neither ovarian nor myometrial involvement. Old pathological studies showed that extragenital cancers rarely spread to genital organs and that in only 4% of them, the uterus represents the unique localization, showing a higher prevalence of myometrial involvement and breast primitiveness [2,3,12]. Starting from the 1999 up-dating review of Piura (3) until June 2023, we performed a MEDLINE (accessed by PubMed) and Google Scholar literature search, using “uterine metastases”, “endometrial metastases” and “breast cancer uterine metastases” as Medical Subject Headings. The search was restricted to recovered full manuscripts in the English language and extended by the checking of Reference lists of identified studies, extracting reports escaped to electronic searches. Only patients with pathologically proven breast cancer spread to endometrium have been included. We identified 57 patients described mainly as case reports, while in eight case series, two patients were described together [6,13-19] (Table 1).

Establishing the true prevalence of breast cancer spreading to endometrium with the sparing of other genital organs is hampered by the clinical assessment of endometrial metastasis. This is often based on the performance of an endometrial biopsy possibly missing concurrent subclinical cervical, myometrial, and adnexal metastatic involvement, ruled out only by the pathological assessment of a Total Hysterectomy and Bilateral Salpingo-Oophorectomy specimen (TH-BSO). In the case presented, the significant rise of CA 125 before endometrial biopsy, leads to hypothesize a subclinical peritoneal surface involvement in metastatic spreading. We declined surgical therapy because of progressive bony disease in the absence of any gynecological symptoms. From the reviewed literature, 30 out of 57 patients (52.6%) with endometrial metastases underwent TH-BSO. Among these women, only 4 (13.3%) showed metastases limited to endometrium without any extragenital localization. In 3 of them, the metastasis was confined within a polyp. A 16-month mean Progression Free Survival (PFS) without evidence of disease was reported in 3 patients whereas follow-up data was unavailable in the fourth woman [20-23]. In the other 26 patients undergoing TH-BSO, concurrent combinations of genital metastases were found beside the endometrial spread. It included myometrium or leiomyomas in 6 patients [13,24-27], myometrium and uterine cervix in 4 [3,17,28,29], myometrium, cervix, and ovary in 8 [16,17,30-35], myometrium and ovary in 4 [7,18,36,37], myometrium and peritoneum in 2 [38,39] and ovary in 2 patients [4,15]. In this group of 26 women, the genital organs represented the only metastatic site in 15 out of 23 evaluable patients (65.2%). Follow-up data were available in 7 out of these 15 patients. Two of them died from disease progression 30 and 48 months later [17] whereas a mean PFS of 10.8 months, without evidence of disease was reported in the remaining 5 patients [3,4,16,24,28].

In women with breast cancer, regular gynecological surveillance is warranted, firstly due to genetic and environmental risk factors shared between breast and endometrial/ovarian malignancies. Moreover, the estrogen pathways activated by Tamoxifen on the endometrium and hypothalamic-pituitary axis either in postmenopausal or premenopausal women enhances the need for planned gynecological consultations [40,41]. However, AUB is the principal complaint needing a quick gynecological investigation. In the reviewed series the first symptom of endometrial metastasis was AUB in 46 out of 57 patients (80.7%). In 11 asymptomatic women, an endometrial biopsy was indicated because of an increased endometrial thickness detected by routine TVU in 8 patients [7,15,18,20,23,30,42,43], a bulky uterine mass in 2 patients [15,27] and an enhanced uterine PET-TC signal in one case [44]. AUB caused by metastatic spread to the endometrium was seldom reported as presenting symptom of unknown breast primitiveness [44-46]. Mostly, AUB due to uterine metastases is a late event of a known breast cancer history and it is often associated with other commonest distant localizations. In 10 out of the 57 patients reviewed, no information about the coexistence of extragenital metastases was provided whereas in 30 out of 47 cases evaluable (63.8%), uterine involvement was synchronous to one or more metastases in extragenital organs. Thirteen of these 30 patients underwent TH-BSO and for 6 of them follow-up data were available. A mean PFS of 17 months was found in 3 patients [15,32,36] whereas 3 patients died from progressive disease 5, 6, and 18 months following the diagnosis of uterine metastases [7,33,34].

Before the diagnosis of endometrial metastasis, our patient underwent Tamoxifen therapy lasting 8 months. From the examined literature, at the time of the diagnosis, 26 out of 57 patients were currently taking Tamoxifen and in 5 patients a previous administration of the drug was recorded [17,22,28,32,39]. Thus, 31 out of 57 patients with metastatic breast cancer to the endometrium (54.3%) experienced exposure to Tamoxifen. It is well known that Tamoxifen can promote endometrial proliferative disorders, including the growth of endometrial polyps (9). Genital breast cancer metastases limited to an endometrial polyp were found in 9 out of the 57 patients reviewed (15.7%), 7 of whom during Tamoxifen administration [14,18,20,21,47-49]. We can speculate that the angiogenetic properties of tamoxifen on the endometrium and the enhanced vascular network associated with polyp growth might lead to a favorable tissue milieu for cancer cell seeding [50,51]. Nevertheless, endometrial breast cancer spread was also reported in polyps unrelated to Tamoxifen intake [22,52] or in patients undergoing aromatase inhibitors therapy [19,30,31,53,54]. Obviously, based on the lack of prospective controlled trials we cannot conclude that Tamoxifen therapy or polyps associated with its intake might enhance the risk of breast cancer spread to endometrium.

In our patient we diagnosed a bilateral metachronous breast cancer of lobular histology refractory to endocrine, chemotherapy, and cyclin dependent-kinase inhibitor, showing an aggressive behavior leading to the quick development of bony, uterine, and brain metastases. Lobular breast cancer accounts for 10%-15% of breast malignancies and its clinical course is worse with respect to carcinomas showing ductal histology. The loss of E-Cadherin cell-membrane expression, a molecule of pivotal value in the mechanism of cell adhesion, is found in more than 90% of lobular cancer and its inactivation results in the inability of tumor cells to adhere to one another, accounting for the major risk of distant spread [55]. Accordingly, in the series evaluated breast cancer metastases were found to be of lobular and ductal type in 40 (70.1%) and 17 (29.8%) patients, respectively. Whether this finding relates to the major metastatic potential of lobular with respect to ductal tumors rather than a specific biological affinity to genital organs harbored by lobular histology remains to be established.

Hysteroscopy with endometrial biopsy is the current reference tool in investigating endometrial pathologies and in breast cancer people suffering from gynecological complaints, it is of utmost value to carry out concurrent endometrial malignancies. Hysteroscopic-view showing polypoid, papillary, or nodular mucosal overgrowth with cerebroid consistency, focal necrosis, and atypical vascular network are considered diagnostic cornerstones of endometrial carcinomas, although a confirmatory pathologic diagnosis obtained by targeted hysteroscopic biopsy or endometrial curettage is required [10,11,56]. In our patient, an uneventful hysteroscopic imaging, revealing small scattered mucosal thickenings ascribed to Tamoxifen intake resulted unsuspicious for malignancy. In the examined literature, the diagnosis of endometrial metastasis was obtained by blind biopsies in 39 patients, by a TH-BSO carried out without a previous endometrial biopsy in 3 cases, and by a hysteroscopic procedure of endometrial sampling in 15 women. Among these latter, no description was provided about the endoscopic imaging in 2 cases [3,14], uneventful common polyps were described in 8 patients [18,22,28,33,42,52,57], a polypoid endometrium in 3 cases [21,43,58] and a large friable polypoid mass in 1 case [36]. Similar to our findings, several small elevated endometrial nodules were described in 1 patient [47]. Therefore, breast cancer endometrial metastases seldom provide a hysteroscopic view suggesting an endometrial neoplasia [36]. We might assume that unlike common endometrial carcinoma, in which the neoplastic growth affects the gland epithelium leading to an early luminal projection of carcinomatous tissue, breast cancer cells, firstly infiltrating the endometrial stroma by hematogenous or lymphatic spread, can hamper or delay the reliability of hysteroscopic imaging.

The differential diagnosis between endometrial tumors and breast cancer metastasis to the endometrium is of pivotal value to address the appropriate management. Surgical staging represents the first choice in primary uterine neoplasms whereas it needs a careful and tailored assessment in breast cancer patients with uterine spread, often presenting synchronous extragenital metastatic sites more conveniently managed by systemic medical therapies. Besides the H&E, a panel of immunohistochemistry stains can reliably support the diagnosis of breast cancer metastatic localization. GCDFP-15 (Gross Cystic Disease Fluid Protein-15) and GATA-3 expression are known as sensitive biomarkers of mammary primitiveness whereas a negative staining for CD-10 and PAX-8 can exclude a neoplasia of mullerian origin. Moreover, tumor cells’ cytokeratin expression leads to exclude mesenchymal proliferative disorders [59]. In our patient H&E findings, immunohistochemistry positive staining for GATA-3 and cytokeratin pool, combined with no expression of PAX-8 and CD-10, and besides the clinical background, supported the diagnosis of endometrial breast cancer metastasis.

Conclusion

Although rarely described, endometrial metastasis from breast cancer must be known by the attending physicians as a possible cause either of AUB or of abnormal endometrial findings on imaging techniques. Isolated endometrial metastasis is an exceptional finding and such a diagnosis obtained by endometrial biopsy underscores a more extensive gynecologic involvement or extragenital metastases in more than 90% of patients. The differential diagnosis between breast cancer metastasis and endometrial cancer can be reliably supported by an immunohistochemistry study, providing data of utmost value to address the appropriate treatment. Based on clinical background, debulking pelvic surgery in breast cancer patients with metastases confined to the genital tract organs can be considered, firstly in order to stop bleeding symptoms and secondly to limit further disease progression theoretically arising from these metastatic implants.

We thank Caroline Calnan Sagrada, a native English speaker experienced in reviewing medical papers, for the support in English grammar and style revision of the manuscript. We thank the husband of the patient for the permission to publish the manuscript.

Author contributions

G. Garuti: Conceptualization, Writing-Review & Editing

P.F. Sagrada: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis

M. Mirra: Data curation, formal analysis, visualization

E. Marrazzo: Data curation, formal analysis, visualization

S. Migliaccio: Data curation, visualization, editing

I. Bonfanti: Formal analysis, visualization, data curation

M. Soligo: Supervision, visualization, validation

The first draft of the manuscript was written by Giancarlo Garuti. All authors and the patient’s husband have read and approved the submitted manuscript

- Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021 May;71(3):209-249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. Epub 2021 Feb 4. PMID: 33538338.

- Kumar NB, Hart WR. Metastases to the uterine corpus from extragenital cancers. A clinicopathologic study of 63 cases. Cancer. 1982 Nov 15;50(10):2163-9. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19821115)50:10<2163::aid-cncr2820501032>3.0.co;2-f. PMID: 7127256.

- Piura B, Yanai-Inbar I, Rabinovich A, Zalmanov S, Goldstein J. Abnormal uterine bleeding as a presenting sign of metastases to the uterine corpus, cervix and vagina in a breast cancer patient on tamoxifen therapy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1999 Mar;83(1):57-61. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(98)00268-1. PMID: 10221611.

- Aksahin A, Colak D, Gureli M, Aykas F, Mutlu H. Endometrial metastases in breast cancer: a rare event. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2013 Jun;287(6):1273-5. doi: 10.1007/s00404-012-2651-5. Epub 2012 Nov 30. PMID: 23197253.

- Rema P, Muralee M, Jayasudha AV, Suchetha S, Ahmed I. Carcinoma breast with endometrial metastasis. Indian J Gynecol Oncol. 2015; 13:20. Doi: 10.1007/s40944-015-0027-z

- Choi S, Joo JW, Do SI, Kim HS. Endometrium-Limited Metastasis of Extragenital Malignancies: A Challenge in the Diagnosis of Endometrial Curettage Specimens. Diagnostics (Basel). 2020 Mar 10;10(3):150. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics10030150. PMID: 32164210; PMCID: PMC7151118.

- Kong D, Dong X, Qin P, Sun D, Zhang Z, Zhang Y, Hao F, Wang M. Asymptomatic uterine metastasis of breast cancer: Case report and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022 Oct 14;101(41):e31061. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000031061. PMID: 36254025; PMCID: PMC9575808.

- Chlebowski RT, Schottinger JE, Shi J, Chung J, Haque R. Aromatase inhibitors, tamoxifen, and endometrial cancer in breast cancer survivors. Cancer. 2015 Jul 1;121(13):2147-55. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29332. Epub 2015 Mar 10. PMID: 25757699; PMCID: PMC4565775.

- Pérez-Medina T, Salazar FJ, San-Frutos L, Ríos M, Jiménez JS, Troyano J, Cayuela E, Iglesias E. Hysteroscopic dynamic assessment of the endometrium in patients treated with long-term tamoxifen. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011 May-Jun;18(3):349-54. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2010.12.014. Epub 2011 Mar 16. PMID: 21411378.

- Garuti G, Sambruni I, Colonnelli M, Luerti M. Accuracy of hysteroscopy in predicting histopathology of endometrium in 1500 women. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2001 May;8(2):207-13. doi: 10.1016/s1074-3804(05)60579-8. PMID: 11342726.

- Di Spiezio Sardo A, De Angelis MC, Della Corte L, Carugno J, Zizolfi B, Guadagno E, Gencarelli A, Cecchi E, Simoncini T, Bifulco G, Zullo F, Insabato L. Should endometrial biopsy under direct hysteroscopic visualization using the grasp technique become the new gold standard for the preoperative evaluation of the patient with endometrial cancer? Gynecol Oncol. 2020 Aug;158(2):347-353. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2020.05.012. Epub 2020 May 25. PMID: 32467056.

- Di Micco R, Santurro L, Gasparri ML, Zuber V, Fiacco E, Gazzetta G, Smart CE, Valentini A, Gentilini OD. Rare sites of breast cancer metastasis: a review. Transl Cancer Res. 2019 Oct;8(Suppl 5):S518-S552. doi: 10.21037/tcr.2019.07.24. PMID: 35117130; PMCID: PMC8797987.

- Briki R, Cherif O, Bannour B, Hidar S, Boughizane S, Khairi H. Uncommon metastases of invasive lobular breast cancer to the endometrium: a report of two cases and review of the literature. Pan Afr Med J. 2018 Aug 9;30:268. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2018.30.268.16208. PMID: 30637053; PMCID: PMC6317397.

- Houghton JP, Ioffe OB, Silverberg SG, McGrady B, McCluggage WG. Metastatic breast lobular carcinoma involving tamoxifen-associated endometrial polyps: report of two cases and review of tamoxifen-associated polypoid uterine lesions. Mod Pathol. 2003 Apr;16(4):395-8. doi: 10.1097/01.MP.0000062655.62606.86. PMID: 12692205.

- Akhtar A, Ratra A, Puckett Y, Sheikh AB, Ronaghan CA. Synchronous Uterine Metastases from Breast Cancer: Case Study and Literature Review. Cureus. 2017 Nov 13;9(11):e1840. doi: 10.7759/cureus.1840. PMID: 29344435; PMCID: PMC5766353.

- Giordano G, Gnetti L, Ricci R, Merisio C, Melpignano M. Metastatic extragenital neoplasms to the uterus: a clinicopathologic study of four cases. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2006 Jan-Feb;16 Suppl 1:433-8. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2006.00235.x. PMID: 16515640.

- Scopa CD, Aletra C, Lifschitz-Mercer B, Czernobilsky B. Metastases of breast carcinoma to the uterus. Report of two cases, one harboring a primary endometrioid carcinoma, with review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol. 2005 Feb;96(2):543-7. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.09.064. PMID: 15661249.

- Martinez MR, Marazuela MA, Vallejo MR, Bernabeu RÁ, Medina TP. Metastasis of lobular breast cancer to endometrial polyps with and without the presence of vaginal bleeding. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2016 Jul;134(1):101-2. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2016.01.005. Epub 2016 Mar 11. PMID: 27045079.

- Akinpeloye A, Satti M, Congdon D, Boike G. Breast cancer masquerades as an endometrial cancer. Obstet Gynecol Cases Rev. 2017; 4: 103. Doi: 10.23937/2377-9004/1410103

- Acikalin MF, Oner U, Tekin B, Yavuz E, Cengiz O. Metastasis from breast carcinoma to a tamoxifen-related endometrial polyp. Gynecol Oncol. 2005 Jun;97(3):946-8. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.03.019. PMID: 15896832.

- Lambot MA, Eddafali B, Simon P, Fayt I, Noël JC. Metastasis from apocrine carcinoma of the breast to an endometrial polyp. Virchows Arch. 2001 May;438(5):517-8. doi: 10.1007/s004280000379. PMID: 11407483.

- Arif SH, Mohammed AA, Mohammed FR. Metastatic invasive lobular carcinoma of the breast to the endometrium presenting with abnormal uterine bleeding; Case report. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2020 Feb 3;51:41-43. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2020.01.008. PMID: 32071717; PMCID: PMC7015833.

- Horn LC, Einenkel J, Baier D. Endometrial metastasis from breast cancer in a patient receiving tamoxifen therapy. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2000;50(2):136-8. doi: 10.1159/000010299. PMID: 10965200.

- Azhar M, Hamdani SAM, Iftikhar J, Ahmad W, Mushtaq S, Kalsoom Awan UE. An Unusual Occurrence of Uterine Metastases in a Case of Invasive Ductal Breast Carcinoma. Cureus. 2021 Nov 22;13(11):e19820. doi: 10.7759/cureus.19820. PMID: 34963837; PMCID: PMC8695695.

- Huo Z, Gao Y, Zuo W, Zheng G, Kong R. Metastases of basal-like breast invasive ductal carcinoma to the endometrium: A case report and review of the literature. Thorac Cancer. 2015 Jul;6(4):548-52. doi: 10.1111/1759-7714.12195. Epub 2015 Jul 2. PMID: 26273414; PMCID: PMC4511337.

- Ertas IE, Sayhan S, Karagoz G, Yildirim Y. Signet-ring cell carcinoma of the breast with uterine metastasis treated with extensive cytoreductive surgery: a case report and brief review of the literature. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2012 Jun;38(6):948-52. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2011.01807.x. Epub 2012 Apr 9. PMID: 22486859.

- Toyoshima M, Iwahashi H, Shima T, Hayasaka A, Kudo T, Makino H, Igeta S, Matsuura R, Ishigaki N, Akagi K, Sakurada J, Suzuki H, Yoshinaga K. Solitary uterine metastasis of invasive lobular carcinoma after adjuvant endocrine therapy: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2015 Feb 14;9:47. doi: 10.1186/s13256-014-0511-6. PMID: 25881005; PMCID: PMC4351848.

- Razia S, Nakayama K, Tsukao M, Nakamura K, Ishikawa M, Ishibashi T, Ishikawa N, Sanuki K, Yamashita H, Ono R, Hossain MM, Minamoto T, Kyo S. Metastasis of breast cancer to an endometrial polyp, the cervix and a leiomyoma: A case report and review of the literature. Oncol Lett. 2017 Oct;14(4):4585-4592. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.6822. Epub 2017 Aug 24. PMID: 29085457; PMCID: PMC5649554.

- Farkas A, Rigney D, Shenoy V, Nutter K. Breast cancer metastasis to endometrium. Appl Radiol. 2020; 49: 52-53.

- Erkanli S, Kayaselcuk F, Kuscu E, Bolat F, Sakalli H, Haberal A. Lobular carcinoma of the breast metastatic to the uterus in a patient under adjuvant anastrozole therapy. Breast. 2006 Aug;15(4):558-61. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2005.10.008. Epub 2005 Nov 28. PMID: 16311034.

- Ustaalioglu BB, Bilici A, Seker M, Salman T, Gumus M, Barisik NO, Salepci T, Yaylaci M. Metastasis of lobular breast carcinoma to the uterus in a patient under anastrozole therapy. Onkologie. 2009 Jul;32(7):424-6. doi: 10.1159/000218367. Epub 2009 Jun 20. PMID: 19556822.

- Awazu Y, Fukuda T, Imai K, Yamauchi M, Kasai M, Ichimura T, Yasui T, Sumi T. Uterine metastasis of lobular breast carcinoma under tamoxifen therapy: A case report. Mol Clin Oncol. 2021 Dec;15(6):266. doi: 10.3892/mco.2021.2428. Epub 2021 Oct 28. PMID: 34777802; PMCID: PMC8581738.

- Aytekin A, Bilgetekin I, Ciltas A, Ogut B, Coskun U, Benekli M. Lobular breast cancer metastasis to uterus during adjuvant tamoxifen treatment: A case report and review of the literature. J Cancer Res Ther. 2018 Jul-Sep;14(5):1135-1137. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.187235. PMID: 30197363.

- Binstock A, Smith AL, Olawaiye AB. Recurrent breast carcinoma presenting as postmenopausal vaginal bleeding: A case report. Gynecol Oncol Rep. 2013 Jun 24;10:38-40. doi: 10.1016/j.gynor.2013.06.003. PMID: 26096920; PMCID: PMC4458745.

- Chupryna E, Ganovska A, Kirilova I, Kovachev S, Baytchev G. Endometrial and cervical metastases leading to the diagnosis of a primary breast cancer; a case report. Int J Surg Med. 2017; 3: 253-256. Doi: 10.5455/ijsm.endometrial-and-cervical-metastases-primary-breast-cancer

- Berger AA, Matrai CE, Cigler T, Frey MK. Palliative hysterectomy for vaginal bleeding from breast cancer metastatic to the uterus. Ecancermedicalscience. 2018 Feb 14;12:811. doi: 10.3332/ecancer.2018.811. PMID: 29515652; PMCID: PMC5834314.

- Meydanli MM, Karadag N, Ataoglu O, Kafkasli A. Uterine metastasis from infiltrating ductal carcinoma of breast in a patient receiving tamoxifen. Breast. 2002 Aug;11(4):353-6. doi: 10.1054/brst.2002.0447. PMID: 14965695.

- Moey MY, Hassan OA, Papageorgiou CN, Schnepp SL, Hoff JT. The potential role of HER2 upregulation in metastatic breast cancer to the uterus: a case report. Clin Case Rep. 2016 Aug 23;4(10):928-934. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.602. PMID: 27761241; PMCID: PMC5054465.

- Trihia HJ, Gavresea T, Novkovic N, Vorgias G. Lobular carcinoma metastasis to endometrial polyps 19 years after primary diagnosis: a report of an exceptional case. J Clin Obstet Gynecol Infertil. 2017; 1: 1019.

- Pérez-Medina T, Salazar FJ, San-Frutos L, Ríos M, Jiménez JS, Troyano J, Cayuela E, Iglesias E. Hysteroscopic dynamic assessment of the endometrium in patients treated with long-term tamoxifen. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011 May-Jun;18(3):349-54. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2010.12.014. Epub 2011 Mar 16. PMID: 21411378.

- Yamazaki R, Inokuchi M, Ishikawa S, Ayabe T, Jinno H, Iizuka T, Ono M, Myojo S, Uchida S, Matsuzaki T, Tangoku A, Kita M, Sugie T, Fujiwara H. Ovarian hyperstimulation closely associated with resumption of follicular growth after chemotherapy during tamoxifen treatment in premenopausal women with breast cancer: a multicenter retrospective cohort study. BMC Cancer. 2020 Jan 29;20(1):67. doi: 10.1186/s12885-020-6549-5. PMID: 31996163; PMCID: PMC6988323.

- Gaspar NG, De Marchi Triglia R, Laguna Benedetti-Pinto C, Yela DA. Case report: ductal breast cancer with endometrial metastases. Reports in Gynecol Surg. 2022; 5: 38-40. Doi:10.36959/909/471

- Hajal E, Dabaj E, Kassem M, Snaifer E, Ghandour F. Endometrial metastasis from a breast carcinoma simulating a primary uterine malignancy. J Adenocarcinoma. 2017; 2: 1. Doi: 10.21767/2572-309x.100016

- D'souza MM, Sharma R, Tripathi M, Saw SK, Anand A, Singh D, Mondal A. Cervical and uterine metastasis from carcinoma of breast diagnosed by PET/CT: an unusual presentation. Clin Nucl Med. 2010 Oct;35(10):820-3. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0b013e3181ef0b1b. PMID: 20838299.

- Adjetey V, Reid BA, Graham CT, Taylor AR. Metastatic carcinoma of breast diagnosed following hysteroscopy and endometrial biopsy. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2002 May;22(3):331-2. doi: 10.1080/01443610252971357. PMID: 12521527.

- Rahmani M, Nili F, Tabibian E. Endometrial Metastasis from Ductal Breast Carcinoma: A Case Report with Literature Review. Am J Case Rep. 2018 Apr 27;19:494-499. doi: 10.12659/AJCR.907638. PMID: 29700276; PMCID: PMC5944400.

- Alvarez C, Ortiz-Rey JA, Estévez F, de la Fuente A. Metastatic lobular breast carcinoma to an endometrial polyp diagnosed by hysteroscopic biopsy. Obstet Gynecol. 2003 Nov;102(5 Pt 2):1149-51. PMID: 14607038.

- Keong CP, Kong LS, Ali RM, Hussin H. Diagnostic pitfalls of metastatic lobular breast carcinoma to the endometrium in a patient on longstanding tamoxifen therapy. Mal J Med Health Sci. 2022; 18: 137-139. Doi: 10.47836/mjmhs18.s21.23

- Al-Brahim N, Elavathil LJ. Metastatic breast lobular carcinoma to tamoxifen-associated endometrial polyp: case report and literature review. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2005 Jun;9(3):166-8. doi: 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2005.03.003. PMID: 15944961.

- Hague S, Manek S, Oehler MK, MacKenzie IZ, Bicknell R, Rees MC. Tamoxifen induction of angiogenic factor expression in endometrium. Br J Cancer. 2002 Mar 4;86(5):761-7. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600157. PMID: 11875740; PMCID: PMC2375303.

- Helmestam M, Andersson H, Stavreus-Evers A, Brittebo E, Olovsson M. Tamoxifen modulates cell migration and expression of angiogenesis-related genes in human endometrial endothelial cells. Am J Pathol. 2012 Jun;180(6):2527-35. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.02.026. Epub 2012 Apr 21. PMID: 22531128.

- Manipadam MT, Walter NM, Selvamani B. Lobular carcinoma metastasis to endometrial polyp unrelated to tamoxifen. Report of a case and review of the literature. APMIS. 2008 Jun;116(6):538-40. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2008.00940.x. PMID: 18754330.

- Danolic D, Marcelic L, Alvir I, Mamic I, Susnjar L, Rendic-Miocevic Z, Puljiz M. Rare case of invasive lobular breast cancer metastasis to the endometrium. Lib Oncol. 2020; 48: 116-118. Doi: 10.20471/LO.2020.48.02-03

- Komeda S, Furukawa N, Kasai T, Washida A, Kobayashi H. Uterine metastasis of lobular breast cancer during adjuvant letrozole therapy. Gynecol Case Reports. 2012; 33: 100-101. Doi: 10.3109/01443615.2012.721407

- Pramod N, Nigam A, Basree M, Mawalkar R, Mehra S, Shinde N, Tozbikian G, Williams N, Majumder S, Ramaswamy B. Comprehensive Review of Molecular Mechanisms and Clinical Features of Invasive Lobular Cancer. Oncologist. 2021 Jun;26(6):e943-e953. doi: 10.1002/onco.13734. Epub 2021 Mar 16. PMID: 33641217; PMCID: PMC8176983.

- Garuti G, Sagrada PF, Frigoli A, Fornaciari O, Finco A, Mirra M, Soligo M. Hysteroscopic biopsy compared with endometrial curettage to assess the preoperative rate of atypical hyperplasia underestimating endometrial carcinoma. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2023 Sep;308(3):971-979. doi: 10.1007/s00404-023-07060-2. Epub 2023 May 9. PMID: 37160470.

- Hooker AB, Radder CM, van de Wiel B, Geenen MM. Metastasis from breast cancer to an endometrial polyp; treatment options and follow-up. Report of a case and review of the literature. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2011;32(2):228-30. PMID: 21614926.

- Famoriyo A, Sawant S, Banfield PJ. Abnormal uterine bleeding as a presentation of metastatic breast disease in a patient with advanced breast cancer on tamoxifen therapy. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2004 Nov;270(3):192-3. doi: 10.1007/s00404-003-0500-2. Epub 2004 Jan 20. PMID: 14735373.

- Salati SA, Alfehaid M, Alsulaim LS, Alsuwaydani SA, Elmuttalut MA. Uterine metastasis from carcinoma of breast: a systematic analysis. J Anal Oncol 2023; 12: 53-71. Doi: 10.30683/1927-7229.2023.12.07

- Gomez M, Whitting K, Naous R. Lobular breast carcinoma metastatic to the endometrium in a patient under tamoxifen therapy: A case report. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2020 Feb 16;8:2050313X20907208. doi: 10.1177/2050313X20907208. PMID: 32110411; PMCID: PMC7026837.

- Karvouni E, Papakonstantinou K, Dimopoulou C, Kairi-Vassilatou E, Hasiakos D, Gennatas CG, Kondi-Paphiti A. Abnormal uterine bleeding as a presentation of metastatic breast disease in a patient with advanced breast cancer. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2009 Feb;279(2):199-201. doi: 10.1007/s00404-008-0665-9. Epub 2008 May 10. PMID: 18470523.

- Franco-Márquez R, Torres-Gaytán AG, Narro-Martinez MA, Carrasco-Chapa A, Núñez BG, Boland-Rodriguez E. Metastasis of Breast Lobular Carcinoma to Endometrium Presenting as Recurrent Abnormal Uterine Bleeding: A Case Report and Review of Literature. Case Rep Pathol. 2019 Feb 24;2019:5357194. doi: 10.1155/2019/5357194. PMID: 30918738; PMCID: PMC6409063.

- Bezpalko K, Mohamed MA, Mercer L, McCann M, Elghawy K, Wilson K. Concomitant endometrial and gallbladder metastasis in advanced multiple metastatic invasive lobular carcinoma of the breast: A rare case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015;14:141-5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2015.07.036. Epub 2015 Aug 3. PMID: 26275738; PMCID: PMC4573862.

- Hara F, Kiyoto S, Takabatake D, Takashima S, Aogi K, Ohsumi S, Teramoto N, Nishimura R, Takashima S. Endometrial Metastasis from Breast Cancer during Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy. Case Rep Oncol. 2010 Apr 29;3(2):137-141. doi: 10.1159/000313921. PMID: 20740186; PMCID: PMC2919989.

Article Alerts

Subscribe to our articles alerts and stay tuned.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Save to Mendeley

Save to Mendeley