Journal of Gynecological Research and Obstetrics

Case Report: Pelvic abscess formation secondary to the use of commercial hemostatic topical agent in an immunocompromised patient?

1ABC Medical Center, México City, Mexico

2American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Mexico

3American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopy, Mexico

Author and article information

Cite this as

Monzón-Vargas M, Gómez-Meraz Y, Ayala-Yáñez R (2017) Case Report: Pelvic abscess formation secondary to the use of commercial hemostatic topical agent in an immunocompromised patient?. J Gynecol Res Obstet. 2017; 3(3): 075-078. Available from: 10.17352/jgro.000043

Copyright License

© 2017 Monzón-Vargas M, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.Various hemostatic agents are currently available for routine laparoscopic procedures, avoiding thermal lesions due to energy devices and the complexity of intracorporeal sutures, however, evidence of complications in immunocompromised patients is still lacking. We present the case of a severely immunocompromised gynecological patient who underwent a routine laparoscopic cystectomy, where a local hemostatic agent was employed; further complications arose, a second diagnostic laparoscopy revealed a pelvic abscess with severe adhesion formation. All under a complicated clinical setting due to an impaired immune response, whether this abscess was caused due to the hemostatic agent or other patient’s conditions remains to be determined, still, various clinical factors and patient’s response need to be taken into account as the cause of the abscess formation.

Bleeding control is one of the most important goals during any surgery. Alternative to the standard suture materials and energy devices, a great variety of topical hemostatic agents and tissue adhesives are currently available as to improve outcomes such as reduced blood loss, need for blood transfusion, shorter surgery times and risk for reintervention [1,2].

At present, precise indications should be followed since complications may arise as we show in the following case report. The aim of this article is to review the medical and scientific information regarding hemostatic agents.

We present a rare case in an immunocompromised patient who underwent a cystectomy, laparoscopic surgery in which the topical hemostatic agent “Surgiflo®” was used to stop oozing. Patient’s outcome was complicated with a pelvic abscess and severe adhesion process that required an open surgical intervention.

Case Report

We present the case of a 26-year- old woman, nulligravida with relevant clinical history of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), chronic anemia, hypertension, and diabetes and end stage renal disease, treated with renal transplant complicated with chronic allograft rejection that conditioned her to require hemodialysis 3 times per week. Current medications include: Tacrolimus, Azathioprine, and Prednisone.

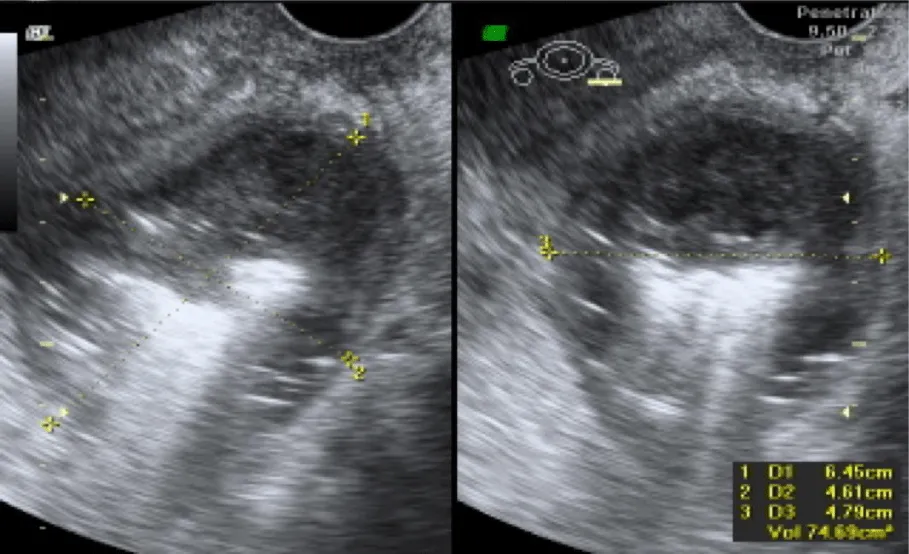

Clinical findings on admission were: acute pelvic pain accompanied with profuse transvaginal bleeding. Endovaginal ultrasonogram revealed the presence of a 6 cm cystadenoma in the left ovary and free fluid in the pelvic cavity. All her laboratory tests were normal, no sign of infection was recorded previous to the surgical procedure.

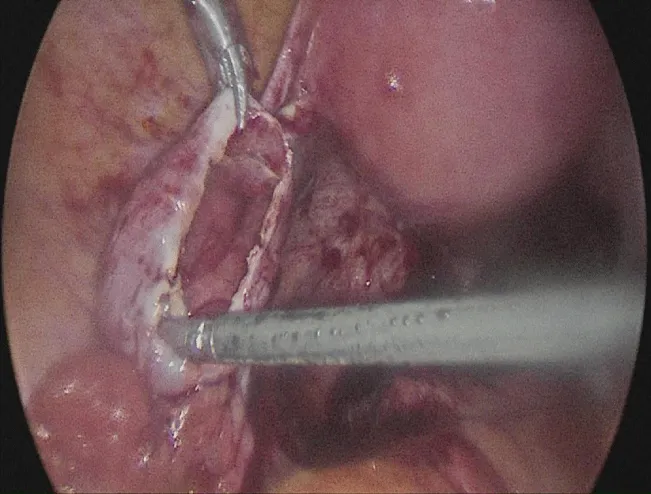

Laparoscopic findings were compatible with endometriosis, adhesions in the cul de sac were identified and surgery was performed with Thunderbeat® energy device. Aspiration and capsule resection completed the procedure (Figure 1).

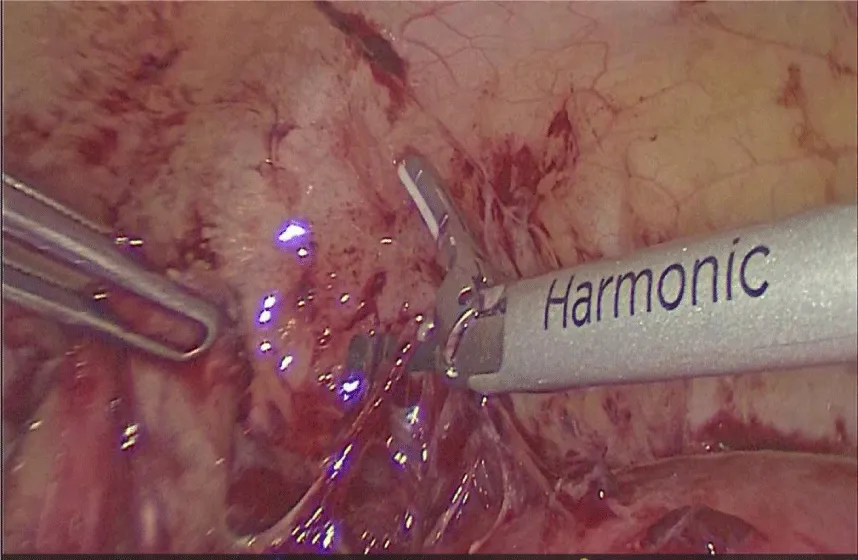

Despite initial hemostasis, posterior cul de sac (where the adhesiolysis took place) presented oozing and the topical hemostatic agent Surgiflo® was applied to prevent hematoma formation, achieving adequate hemostasis (Figure 2). Patient was discharged 2 days later, developing urinary tract infection positive for Ureaplasma urealyticum that was treated with broad spectrum antibiotics.

Fourteen days later Bacteroides fragilis was inoculated in a blood sample and was treated with vancomycin and ertapenem. Patient´s response wasn´t satisfactory despite all the precautions and multidisciplinary approaches. She continued to have intermittent fever and diarrhea (although all her coprological cultures were negative).

After four weeks, the patient was readmitted due to the presence of persistent fever and pelvic pain. Laboratory tests reported slightly increased leucocytes (9.7 x 103 µL), low hemoglobin of (7.3 g/dL), 3 bands, procalcitonin of 0.6 ng/mL and an elevated C reactive protein (CPR, 13.97mg/dL). Blood, urine, stool and cervicovaginal cultures were negative. Ultrasound reported a 7 cm, diameter collection with heterogeneous characteristics with fluid contents located in the posterior cul de sac, compatible with remnants of a hemostatic agent (Figure 3).

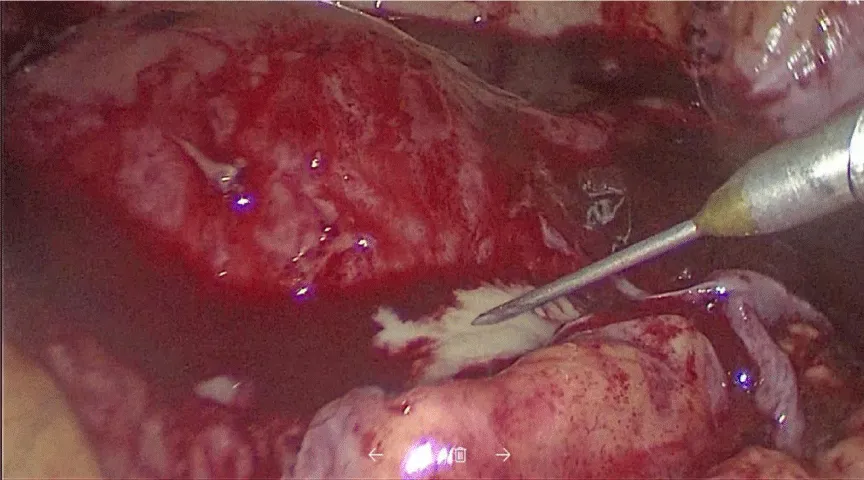

Since the etiology of the fever wasn’t determined a second diagnostic laparoscopy was performed. During this procedure, multiple adhesions that distorted normal anatomy were identified, an abscess of 2 cm in diameter was found in the posterior cul de sac firmly attached to the left ovary and rectum. Due to the severe adhesion process, laparotomy conversion was opted. In the open procedure, adhesion removal and exhaustive pelvic cavity lavage were performed, the abscess drained 15 mL of purulent material with no characteristic smell, samples were taken for microbiologic cultures (Figures 4,5), (no pathogen was isolated). A sponge like material was found and taken out of the posterior cul de sac, compatible with the common degradation process of the hemostatic agent. Parenteral antimicrobial medication was initiated with adequate response, discharging the patient 1 week later. No further complications were reported.

Discussion

This clinical case presents a severely immunocompromised woman who was attended for a relatively common gynecological condition and subsequently complicated with a pelvic abscess and adhesion process.

The possible associations of hemostatic agents with infective complications are listed as follows:

1. Histologic changes with granulomatous reaction secondary to foreign material [3].

2. Delayed time of absorption of some hemostatic agents. [4-6].

3. Biological material agents are prompt for colonization serving as culture media [7,8].

4. Incorrect amounts and disposal of hemostatic agents may lead to adhesion formation [7,9].

5. Some agents promote a diminished pH on nearby environments, disrupting local innate defense immune mechanisms such as protease activity [1,10]. On the other hand, oxidized regenerated cellulose hemostatics are considered bactericidal, due to their acidification of the media [2].

Previous studies performed on immunocompetent patients identified risk factors for abscess formation such as untreated pelvic inflammatory disease, endometriosis, previous laparotomy and post-operative hematomas [11-13]. Hemostatic agents have been suggested as an added risk factor for infection in these clinical settings; however, we currently lack quality evidence to support this statement. Additionally, studies that address this question in immunocompromised subjects are needed.

Clinical benefits of the hemostatic agents, supported by existing studies are: a) preventing thermal damage on vascular and nerve structures (as when electrosurgery is employed), b) achieving early and adequate hemostatic control in friable tissues and c) better outcomes in patients with hemorrhagic diathesis [14-16].

Risk of infection secondary to fluid hemostatics such as Floseal ® or Surgiflo ® may be minimized by removing the excess of this topical hemostatic agent from the wound after hemostasis is achieved, since excessive amounts of slowly degrading products can serve as a site for infection development [17,18]. Considering other options for wound hemostatic products who may minimize the risk of infection due to their structural characteristics are: AristaTM (purified plant starch, microporous polysaccharide hemospheres), Surgicel (polyanhydroglucuronic acid with bactericidal capacity) and Surgicel SNoWTM (oxidized regenerated cellulose) and these agents have bacteriostatic properties and are in a dry state when applied. Although physical characteristics have not been proven to diminish infections, they do suggest decreased complications.

In this case, the underlying clinical conditions placed the patient at higher risk for any type of infection in comparison with the rest of the population, hence, secondary abscess formation couldn’t be established with certainty.

Finally, current guidelines on late abdominal sepsis state that a possible mechanism explaining the presence of anaerobic pathogens like the one found in this case, is bacterial translocation which presumably caused bacteremia with B. fragilis. No pathogen was inoculated in the second procedure probably due to the previous administration of broad spectrum antibiotics.

Conclusion

Because of the insufficient evidence available, the authors’ recommendation is to avoid excessive use of this type of hemostatic in immunocompromised patients.

If strictly necessary, and the patient’s condition warrants it, we suggest choosing a rapid resorption hemostat such as Microporous Polysaccharide Spheres like Arista ® as first choice, this one shows complete resorption within 48 h vs gelatin matrix agents that can take 6 to 8 weeks to disintegrate. Surplus hemostatic agents should be removed after achieving the desired effect.

- De la Torre RA, Bachman SL, Wheeler AA, Bartow KN, Scott JS (2007) Hemostasis and hemostatic agents in minimally invasive surgery. Surgery 142: S39-S45. Link: https://goo.gl/Cd4vRQ

- Peralta E (2007) Overview of topical hemostatic agents and tissues adhesives. Link: https://goo.gl/Kor8aC

- Shashoua AR, Gill D, Barajas R, Dini M, August C, et al. (2009) Caseating granulomata caused my hemostatic agent posing as metastatic leiomyosarcoma. JSLS 13: 226-228. Link: https://goo.gl/mWKwtB

- Watrowski R, Jäger C, Forster J (2017) Improvement of Perioperative Outcomes in Major Gynecological and Gynecologic – Oncological Surgery with Hemostatic Gelatin – Thrombin Matrix. In Vivo 31: 251- 258 Link: https://goo.gl/rKRLFW

- Duenas-Garcia O, Goldberg JM (2008) Topical Hemostatic Agents in Gynecologic Surgery. Obstet gynecol surv 63: 389-394. Link: https://goo.gl/CvnYDE

- Wysham W, Roque D, Soper J (2004) Use of topical hemostatic agents in gynecologic surgery. Obstet Gynecol Surv 69: 557-563. Link: https://goo.gl/w98CfG

- Hobday D, Milam M, Milam R, Euscher E, Brown J (2009) Postoperative Small Bowel Obstruction Associated with use of Hemostatic Agents. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 16: 224-226. Link: https://goo.gl/gQeaeZ

- Fagotti A, Costantini B, Fanfani F, Vizzielli G, Rossitto C, et al. (2010) Risk of postoperative pelvic abscess in major gynecology oncology surgery: one- year single – institution experience. Ann Surg Oncol 17: 2452-2458. Link: https://goo.gl/hzqqUX

- Cağlar M, Yavuzcan A, Yıldız E, Yılmaz B, Dilbaz S, et al. (2014) Increased adhesion formation after gelatin- thrombin matrix application in a rat model. Arch Gynecol Obstet 290: 501-506. Link: https://goo.gl/G7e7n8

- Camp MA (2014) Hemostatic Agents: A guide to safe practice for perioperative nurses. AORN J 100: 131-147. Link: https://goo.gl/KZcKwX

- Obermair H, Janda M, Obermair A (2016) Real- world surgical outcomes of gelatin – hemostatic matrix in women requiring a hysterectomy: a matched case-control study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 95: 1008-1014. Link: https://goo.gl/npojkP

- Anderson CK, Medlin E, Ferris AF, Sheeder J, Davidson S, et al. (2014) Association between gelatin thrombin matrix use and abscesses in women undergoing pelvic surgery. Obstet Gynecol 124: 589-595. Link: https://goo.gl/4BvJQ8

- Zand B, Frumovitz M, Jofre MF, Nick AM, Dos Reis R, et al. (2012) Risk factors for prolonged hospitalization after gynecologic laparoscopic surgery. Gynecol Oncol 126: 428-431. Link: https://goo.gl/bQBfc8

- Schreiber MA, Neveleff DJ (2011) Achieving Hemostasis with Topical Hemostats: Making Clinically and Economically Appropriate Decisions in the Surgical and Trauma Settings. AORN J 94: S1-S20. Link: https://goo.gl/apU8A2

- Parker WH, Wagner WH (2010) Gynecologic surgery and the management of hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 37: 427-436. Link: https://goo.gl/USjK2N

- Wright JD, Ananth CV, Lewin SN, Burke WM, Siddinq Z, et al. (2014) Patterns of use of hemostatic agents in patients undergoing major surgery. Journal Surg Res 186: 458-466. Link: https://goo.gl/nqsUdY

- Link: https://goo.gl/CSMU1x

- Baxter Healthcare: Floseal® hemostatic matrix, instructions for use. Link: https://goo.gl/Y3mdcK

Article Alerts

Subscribe to our articles alerts and stay tuned.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Save to Mendeley

Save to Mendeley