Journal of Gynecological Research and Obstetrics

High Reproductive Risk and Contraception

Alexander Porter Magaña1, Suria Denisse Soriano León1, Víctor Manuel Vargas Hernández2*

1Hospital General Regional, Mr. Ignacio García Téllez, Mexican Social Security Institute, Mexico

2Mexican Academy of Surgery, National Academy of Medicine of Mexico, Mexico

Cite this as

Magaña AP, Soriano León SD, Vargas Hernández VM. High Reproductive Risk and Contraception. J Gynecol Res Obstet. 2025;11(1):006-010. Available from: 10.17352/jgro.000132Copyright License

© 2025 Magaña AP, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.Background: Patients with high reproductive risk have important risk factors for the development of complications, including maternal death. Rejection of contraceptive methods is influenced by biological, cultural, and social factors.

Objective: Identify the main sociocultural and demographic factors associated with not choosing a contraceptive method in women at high reproductive risk.

Material and methods: it is an observational, cross-sectional, analytical and prospective study using non-probabilistic sampling of pregnant women with high reproductive risk who were offered contraception through a questionnaire.

Results: 75 patients with high reproductive risk (20%) were included, with a mean age of 27 years and 48% identifying as housewives, living in an urban area (66.7%), complete primary schooling (22.67%), Catholic religion (72%), married (57.3%), middle class (72%); alcoholism in 2 patients (2.67%) and 2 other drugs (2.67%); 68% rejected contraception; for personal reasons (76.4%). A significant relationship was found with the Jehovah’s Witness religion (p = 0.018).

Conclusion: Rejection of contraception was significantly associated with personal history and religious beliefs, with implications for reproductive health.

Background

The History of human contraception (CA) has the purpose of achieving sexual pleasure, avoiding fertilization [1]. In The Papyrus of Petri, from 1850 BC, contraceptive recipes already appeared; crocodile excrement, pessary [2], coitus interruptus, [1] condom [2] spermicides with vinegar, [2]. The intrauterine device emerged in 1863 [2]. In 1934, progesterone was isolated and in 1956 the pill was discovered [2]. Surgical techniques began at the end of the 19th century, with female sterilization and later vasectomy [1], under informed consent [3].

AC constitutes the fundamental basis of reproductive health (RH); the benefits include the reduction of poverty, maternal and perinatal mortality, with a better quality of life, greater opportunities for education, work, and an equal society. In Mexico with more than 35 years in the promotion and improvement of CA, with changes in the legal and public health framework; In 1973, it was the second in the world and first in Latin America to establish in its Constitution the right to decide in a free, responsible and informed manner about the number and spacing of their children (Article 4 of the political constitution of the United Mexican States). In 1974, population growth was regulated within the General Population Law, with a National Family Planning Plan (1977–1979), which resulted in the reduction of the global fertility rate from 7.26 children per woman in 1962 to 3.43 in 1990, and to 2.01 in 2012 [4]; However, over the past 12 years, a slowdown has been observed. Contraceptive coverage for women increased from 15.0% in 1973 to 74.5% in 2003 to decrease to 70.9% in 2006; reporting 72.5% in 2009 [4]; According to the National Demographic Dynamics Survey (ENADID) 2018, the median age at the beginning of sexual life is 17.5 years, of which 59.4% did not use any contraceptive method. Among women between 15 and 49 years old, they did not use a contraceptive method in their first sexual relationship, due to unplanned sexual encounters (28.4%), followed by a desire for pregnancy (24.3%), lack of knowledge about contraceptive methods (24.1%), hoping not to get pregnant (11%), and other reasons (10.9%) [5].

Globally, it is estimated that 214 million women of reproductive age have unmet needs for contraception in emerging countries and 67 million unplanned pregnancies, 36 million induced abortions and 76 thousand maternal deaths could be avoided each year [6,7].

The reasons why women and their partners do not use contraceptive methods are multiple. In sub-Saharan Africa, for example, low use of the contraceptive method, fear of adverse effects, lack of partner approval due to social and cultural beliefs that include traditional abstinence practices waiting for the return of menstruation to initiate contraceptive use. These are misconceptions, and monitoring improves the continuity of contraceptives.

The World Health Organization established the medical eligibility criteria for the use of contraceptives according to the health conditions of each patient and considering special situations. The use of modern contraceptives is associated with sociodemographic, sociocultural and economic factors [8]. The evaluation of reproductive risk, a method that allows measuring care needs, helps determine health priorities, it is about having sufficient coverage and information for each woman with high reproductive risk, to reduce perinatal maternal morbidity and mortality and complications due to reproductive risks., which is defined as the probability that a woman has of suffering damage during the reproduction process, which affects the mother, the fetus or the newborn, with an increased risk of maternal morbidity and death [9]; the identification of pathologies or high reproductive risk, such as chronic non-communicable diseases, which are rare in reproductive age. There are many factors that are related to definitive sterilization; Married women are the ones who most opt for this method, the couple, for emotional and economic support; Unlike single women, the sexual behavior of the couple influences; Women who reject this definitive method, some women cite fears of side effects, breastfeeding interference, or transition to menopause [4], other reasons include: illness of the partner (which limits the frequency of sexual relations) , infrequent or non-existent sexual relations, a couple who travels for long periods of time, interrupted intercourse or because their partner does not agree, formal education, place of residence and socioeconomic level, influence the choice of a contraceptive method [4] . Society and culture influence family size, family pressures to have children, customs and religious beliefs [10] particularly in societies where patriarchal norms dominate [11]; Maternal mortality rates (MMR) between countries, and even between different regions of the same country, show their intrinsic link with poverty and marginalization [12].

Maternal death worldwide is unacceptably high, every day around 830 women die worldwide from complications related to pregnancy, childbirth or the postpartum period; All of these deaths occur in emerging countries and the majority are avoidable [13]. In Mexico it was reported in 2017; 20.8 deaths per 100 thousand estimated births; mainly those between 45 and 49 years old [14] and from 2013 to 2015 in Yucatán it was 43. 5 [15]; various preventive actions to reduce maternal mortality; a) promote prenatal care and b) prevent pregnancies in patients who have risk factors. Contraception has the potential to save millions of women’s and infants’ lives, determining the health and economic well-being of millions of families.

Material and methods

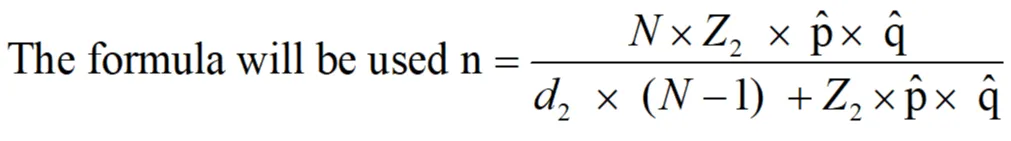

An observational, analytical, cross-sectional, prospective study was carried out; at the Dr. Ignacio García Tellez Regional General Hospital (T-1) Mexican Social Security Institute (IMSS) of Mérida Yucatán; in the gynecology and obstetrics outpatient clinic during the period from June 2022 to June 2023; in pregnant women at high reproductive risk. In 5938 of pregnant patients (N); a confidence level of 95% (Z = 1.96), a proportion of 50% (p̂ = 0.5), therefore, a proportion complement of 0.5 (q̂ = 1- p̂) and an error of 5% (d = 0.05) for finite population.

n = sample size

N = total population for one year.

Z = critical Z value, calculated from the area under the curve tables. Confidence level.

p̂ = approximate proportion of the phenomenon under study in the reference population

q̂ = proportion of the reference population that does not present the phenomenon under study

(1 p).

d = absolute precision level.

Resulting in a sample of 360 patients. The sampling was non-probabilistic. The use of non-probabilistic sampling in this study allowed for targeted data collection focused on pregnant women at high reproductive risk, ensuring the findings are relevant to this specific population. This approach was feasible and practical in the clinical setting. However, it introduces limitations, including potential selection bias and reduced generalizability, as the sample may not represent the broader population. Additionally, non-probabilistic sampling may restrict the scope of statistical analyses and inadvertently exclude individuals with varying risk factors beyond the defined criteria. To determine patients with “reproductive risk” the Manual of family planning procedures in the units of the Mexican Social Security Institute, code 2230-003-001, Table 1, was used.

The protocol was submitted to review by the hospital’s research and ethics committees. The reproductive risk survey was applied to 360 patients from the obstetrics outpatient clinic who met the selection criteria, studying those who had a reproductive risk greater than or equal to 4 points, which was a total of 75 patients. A second questionnaire was administered to the 75 patients with high reproductive risk, in which sociodemographic and family planning data were obtained.

Results

A total of 360 patients who met the previously described selection criteria were interviewed. There were 75 patients included in the study as they presented a reproductive risk greater than 4 and who agreed to participate in the study, which formed the present investigation. The mean age was 27 ± 5.3 years. The most frequent occupation was housewife with 38 patients (48%). Regarding origin, the patients were mostly of urban origin, 50 patients (66.7%). The most frequent education was completed primary school with a frequency of 17 patients (22.67%) followed by bachelor’s degree and high school. The most frequently found religion was Catholic in 54 patients (72%) followed by Christian in 11 occasions (15%). The most frequent marital status was married (57.3%), followed by common-law unions (22.7%) as shown in Table 2.

A descriptive analysis was carried out on the patients who did not accept contraception. The average age was 27.15 years ± 5.29 years. The most frequent occupation was housewife in 25 patients (49%). The most frequent origin was an urban area in 30 patients (58.82%) as shown in Table 3. The most frequent education was complete primary school in 14 patients (27.45%), the same as the education of the rest of the patients.

Regarding the most frequent religion of the patients who did not accept contraception, it was the Catholic religion. The most frequently found marital status was married in 62%, while the socioeconomic level that we found most was medium level in 70%, as reported in Table 4. Analytical statistics were performed with logistic regression, finding a significant statistical association only in the religion variables as shown in Table 5.

Discussion

Of the total of 360 patients interviewed, a high obstetric risk rate was obtained for 75 patients, who were included in the study. Only 24 patients accepted the planning method (32%), and in the reasons of the patients who did not accept the family planning method, personal reasons prevailed, stating that they wanted to have even more children. This indicates that 68% of high-risk patients refused contraception of definitive contraception in high obstetric risk patients. The average age of the sample was 27 years ± 5.3, without finding a statistically significant relationship with the refusal of contraception; similar data in different countries [16,17] did not find an association with age. The most frequent occupation was housewife with 38 patients (48%) also without a significant relationship, similar to others [18]. The origin of the patients was mostly urban areas with 66.7% similar to others [19] who reported 69.5 and 30.5% in rural areas, without finding a significant association with non-acceptance of contraception at the first level of care.

The most common level of education observed was complete primary school. This differs from findings in other studies [20,21], where participants had completed high school or secondary school. This discrepancy may be attributed to regional variations and differences in the average age of the samples, with their participants being older than our average age of 30 to 39 years. These studies reported a significant association with education and refusal to use contraception.

The most frequently found religion was Catholic in 54 patients (72%), similar to others [22]. In our study, a significant association with religion was observed, which contrasts with previous Mexican studies [16,19,21,22], although the significant association was presented with the Jehovah’s Witness religion (p = 0.017), a religion that was not studied in Mexico, unlike others [23] who found a significant association (0.03) with religion on the refusal of contraception [24] where religion was a significant factor in association with non-use of the implant (p = 0.005), in both studies the frequency of patients who were Jehovah’s Witnesses was similar to ours (3 patients and 7 patients respectively).

In most Latin American countries, religion significantly influences contraceptive access, health policy decisions, and health service providers may not offer this type of service for fear of confronting religious institutions.

In general, the most frequently practiced religions in Mexico consider contraception as part of home life and as an important factor in the stability of marriage. The majority agrees in affirming that contraception constitutes an obligation of responsible parenthood, as long as the designs of the church are respected, such is the case of the Catholic Church and Jehovah’s Witnesses, who consider the rhythm method as the only acceptable way. In rural areas, religion plays a significant role in relation to the low prevalence of contraceptive practice, especially when there is low education, in which it is considered that one should not talk about issues related to sexuality or contraception [25].

The most frequent marital status was married in 43 cases (57.3%), others did not find a similar association in 41 patients being married, the most frequent marital status being. Marital status is a condition that influences the use or non-use of methods, and it is reported that married women tend to be the most accepting, unlike single women who may face social stigma; however, this factor did not significantly influence our sample.

Regarding the socioeconomic level of the patients, the most frequently found was middle class in 54 patients (72%), in both cases without a statistically significant relationship, similar to others [26] who found the low middle socioeconomic level as the most frequent in its population of first-level care female patients who did not accept contraceptives, without finding a relationship with statistical significance (OR 0.33, p 0.18, CI 0.06-1.81). with similar results to others in that the majority of their respondents in Zacatecas reported no alcohol or drug use (OR 0.58, p 1.16, CI 0.22 - 1.55) comparable to the 2 patients (2.67%), and 2 patients ( 2.67%) reported drug use in our study without finding a significant association in any of these variables.

Conclusion

The frequency of high reproductive risk in pregnant women, the sociodemographic characteristics of patients with refusal of contraception in patients with high reproductive risk, a significant relationship was only found with Jehovah’s Witness religion.

Job limitations

One of the main limitations of the present work is that it is a non-randomized study, which could obtain more precise information with randomized controlled clinical studies, in addition to being a study was limited to a single secondary-level medical center, more representative results can be obtained from multicenter studies at the regional or even national level.

Strengths

The present study has the strength of being prospective, with broad sampling, obtaining data from direct interviews, another strength is having considered various variables probably related to the refusal to use the family planning method, in addition to carrying out a multivariate analysis with regression logistics, avoiding confounding variables.

Recommendations

It is recommended to carry out new studies, this time considering intervention type studies, seeking to reduce the rate of refusal to use definitive contraception, in addition to raising the possibility of carrying out long-term follow-up cohort studies, investigating the degree of obstetric complications, as in Kaplan Mayer curve studies.

Derived from the results, both the obstetric risk rate and the rate of refusal to use contraception are worrying, so it is essential to increase awareness among high-risk patients about potential complications from subsequent pregnancies. Likewise, it would be important to work with the population of religions such as Jehovah’s Witnesses, which proved to be a variable associated with the refusal of contraception.

- Núñez JA. Evolutionary history of contraception. Royal National Academy of Medicine of Spain. 2018;56–9.

- Díaz Alonso G. History of contraception. Cuban J Compr Gen Med. 1995;11(2):192–4.

- Ministry of Health and Social Welfare. Family Planning Manual. 2016.

- Allen-Leigh B, Villalobos-Hernández A, Hernández-Serrato MI, Suárez L, De la Vara E, De Castro F, et al. Onset of sexual activity, contraceptive use, and family planning in adolescent and adult women in Mexico. Salud Publica Mex. 2013;55(Suppl 2):S235–40. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24626700/

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). National Demographic Dynamics Survey (ENADID). Mexico; 2018.

- Cavallaro FL, Benova L, Owolabi OO, Ali M. A systematic review of the effectiveness of counseling strategies for modern contraceptive methods: What works and what doesn’t? BMJ Sex Reprod Health. 2020;46(4):254–69. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjsrh-2019-200377

- Barrera Coello L, Olvera Rodríguez V, Castelo-Branco Flores C, Cancelo Hidalgo MJ. Reasons for discontinuing contraceptive methods. Ginecol Obstet Mex. 2019;87(Suppl 1):S128–35.

- Capella D, Schilling A, Villaroel C. Medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use by WHO. Chil J Obstet Ginecol. 2017;82(2):212–9.

- Rodriguez ML. Risk-based approach in the reproductive process. Reprod Health Fam Plan. Universidad Los Ángeles de Chimbote. 2010;1–5.

- Suárez Gutiérrez JJ, Rangel Villasenor O. Acceptance rate of definitive family planning methods at ISSEMYM Regional Hospital Tlalnepantla from January 1, 2013, to June 31, 2013. 2014.

- Ráez LE. Voluntary sterilization as a means of family planning [Internet]. Aciprensa; 2019. Available from: https://www.aciprensa.com/recursos/la-esterilizacion-voluntaria-como-mediopara-planificar-la-familia-249

- del Carmen Elu M, Pruneda ES. Maternal mortality: An avoidable tragedy. Perinatol Hum Reprod. 2004;18(1):44–52.

- United Nations Population Fund. Sustainable development goals: 17 goals to transform our world. 2025. Available from: http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopmnet/es/summit/

- Directorate General of Epidemiology. Maternal mortality report. 2020.

- Morales-Andrade E, Ayala-Hernández MI, Morales-Valerdi HF, Astorga-Castañeda M, Castro-Herrera GA. Epidemiology of maternal death in Mexico and the fulfillment of Millennium Development Goal 5 towards sustainable development goals. J Med Surg Spec. 2018;23(2):61–86. Available from: https://www.medigraphic.com/cgi-bin/new/resumenI.cgi?IDARTICULO=83252

- Mejia Carlos ML, Pineda Diaz RM. Factors associated with non-use of contraceptive methods during the postpartum period at Victor Ramos Guardia Hospital-Huaraz, 2017. 2018.

- Morante Veliz GV, Vásquez Álvarez AC. Factors influencing the choice of a contraceptive method in women aged 14 to 30 years who attend external consultations at Antonio Sotomayor Health Center, Vinces canton, Los Ríos, January-June 2019. Babahoyo: UTB-FCS; 2020.

- Carrillo Rivas KC, Jarquín Trujillo HM. Social and cultural factors in the use of contraceptive methods in adolescents attended at the Family Planning Program at El Calvario Health Center, Chinandega, second half of 2019. 2019.

- de la Vega Apanco E. Causes of non-acceptance of family planning methods in women of reproductive age at a first-level care clinic. Mexico City: National Autonomous University of Mexico; 2017.

- Velazquez Mejia B, Reyes Jimenez O, Marquez Gonzalez J. Causes of acceptance and non-acceptance of a family planning method in the postpartum period of patients at UMF 92. Mexico City: National Autonomous University of Mexico; 2021.

- Reyes Aguilar A, Ceja Aladro A. Reasons for non-acceptance of a family planning method in postpartum women at HGZ MF No1 in Pachuca Hidalgo. Mexico City: National Autonomous University of Mexico; 2019.

- Arreola Ávalos MG. Reasons for non-acceptance of family planning methods in women aged 12 to 49 years in the Conca health center, Arroyo Seco, during the period January–February 2013. Mexico City: National Autonomous University of Mexico; 2015. Available from: https://www.onlinescientificresearch.com/articles/high-reproductive-risk-and-contraception.pdf

- Pinta MJL. Contraceptive method choice in a rural population. Knowl Hub Prof Sci J. 2022;7(1):42.

- Xiomara NHS, Lily TMT. Sociocultural factors associated with the non-use of the subdermal implant "Implanon" in women attending family planning at Monterrey Health Center, Huaraz 2019. 2020.

- Mundigo AI. Religion and reproductive health: Crossroads and conflicts. Center for Health and Social Policy. Research meeting on unwanted pregnancy and unsafe abortion. Public health challenges in Latin America and the Caribbean. Mexico City; 2005.

- Ramirez Vázquez MG. Sociocultural factors associated with the non-utilization of family planning methods in adolescents at a first-level care unit. Vol. 2. Mexico City: National Autonomous University of Mexico; 2020.

Article Alerts

Subscribe to our articles alerts and stay tuned.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Save to Mendeley

Save to Mendeley