The Psychological Impact of Unresolved Childhood Trauma in a Pediatric Population

1Institute for the Study of Psychotherapies - ISP, Rome, Italy

2Sapienza University of Rome, Rome, Italy

Author and article information

Cite this as

Perrotta G, et al. The Psychological Impact of Unresolved Childhood Trauma in a Pediatric Population. Open J Trauma. 2025; 9(1): 032-042. Available from: 10.17352/ojt.000051

Copyright License

© 2025 Perrotta G, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.Introduction: Unresolved childhood traumas, throughout the human developmental stage, are capable of negatively affecting an individual’s psychophysical growth, promoting the onset of psychopathological conditions. In the literature, the intrapsychic processes capable of explaining this phenomenon are not yet known, and the specific consequences are not known with certainty.

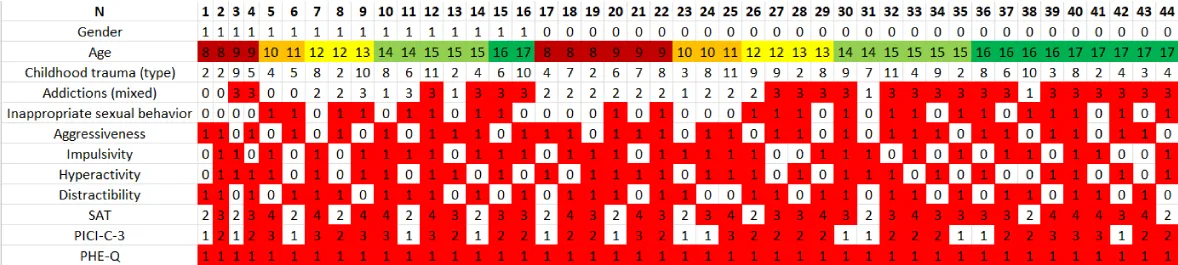

Method: The sample is composed of 44 Italian participants (16 males; 28 females), aged between 8 and 17 years (M: 12.9; SD: 3.1). By means of clinical interview and administration of the “Test of Separation Anxiety” (SAT), the “Perrotta Integrative Clinical Interviews”, version C-3 (PICI-C-3) and the “Perrotta Human Emotions Questionnaire” (PHE-Q), pediatric patients included in the population sample were investigated.

Results: The data obtained from the research statistically showed significant differences (p < 0.001) between the clinical group and the control group, correlating pathological attachment style with a specific dysfunctional personality profile (p < 0.001), in the pediatric population studied.

Conclusions: Unresolved childhood trauma is a predisposing factor for the onset of a psychopathological disorder, capable of impacting both functioning and personality structure; however, other factors have also been identified that, if present facilitate or exacerbate the morbid condition, such as the duration of exposure to the trauma, the repetitiveness of the negative effects of the trauma, the depth of the suffering experienced, possible behavioral reinforcers, other traumatizing causes, such as psychophysical violence (with or without sexual intent), genetic and familial predisposition to certain psychopathologies, extreme economic poverty, adverse socio-environmental and cultural context, and difficulty of integration. Early psychotherapeutic intervention can promote functional recovery.

Key points:

Unresolved childhood traumas are factors that predispose the onset of psychopathologies, but require other contributing causes to exert their dysfunctional power.

Unresolved childhood traumas influence neuropsychological development from their onset.

Unresolved childhood trauma has a greater negative impact, regardless of age, if it is amplified or maintained by other predisposing or facilitating factors, such as education received, personal and family lifestyle, social environment, and genetic predisposition.

Sexual gender (male/female) does not play an important role in unprocessed childhood trauma, except to the extent of the sexual sphere, with a marked prevalence in the female population.

SAT: Separation Anxiety Test; PICI-C-3: Perrotta Integrative Clinical Interviews; PHE-Q: Perrotta Human Emotions Questionnaire; CG: Clinical group; Cg: Control group

Introduction

Background

The definition of “psychological trauma”, shared by the majority of literature, is that offered by the French psychodynamic school of Pierre Janet, which identifies it as one or more events which, due to their intrinsic characteristics, can alter the subject’s psychic system, threatening to fragmenting cohesion and mental stability, effectively generating what he defined as traumatic hysteria and which today is packaged in its severe form in post-traumatic stress disorder [1]. Ivan Pavlov, on the other hand, considered trauma only as an innate defensive reaction in response to environmental threats, which presented lasting psychophysical alterations over time and this position is shared by the writer [2], as psychological trauma is not capable of only to generate a stable and lasting disorder or even impact on the personality, unless this presents specific conditions: a) subjective severity of the trauma (the more serious it is perceived by the subject, the more it is able to invalidate individual psychophysical growth ); b) onset at a young age (the more the trauma occurs in childhood, the more the emotional scars remain, especially unconscious ones); c) impact on the figures of reference (the more the trauma impacts on the figures of reference, because they are the cause or suffer the effects as in the case of an illness and/or a fatal event, the more the subject will perceive anguish); d) duration of the traumatic event (the more the trauma persists over time or is strengthened with repeated conduct, the more the trauma will exert its effects on the structural and functional elements of personality).

It can therefore be stated that the traumatic event, subjectively perceived, is represented by one or more events experienced by the subject as “critical, i.e., capable of generating anguish which manifests itself mainly in the form of impotence, anger, fear, sadness, and vulnerability, and capable of threatening the integrity of the person’s psychophysical balance. The traumatic event, from a structural point of view, can be of any type: it can concern the loss of a loved one, as happens in a separation or during a death mourning, or even for the loss of chance in the conclusion of a professional service that was important for the subject, or even a serious illness or a violent event such as sexual violence or events with a strong psychological impact, as in the case of domestic and family violence, verbal violence and bullying) [3]. All these hypotheses, heterogeneous in their representation, are, however, characterized by a common element: essentially, the event modifies the subject’s perception of well-being, making it more fragile and unstable, distorting its identity (in the most serious cases) and turning him into a “victim”. Therefore, if the traumatic event is not processed correctly, this condition can become chronic over time, even rapidly, generating a real dysfunctional distortion in the subject, which may or may not also impact the stability of the personality [4].

Indeed, several studies published between 2014 and 2018 [5-8] have shown that traumas can be passed down from generation to generation, up to the third, according to the mechanism of heredity and this process seems to be hidden in “microRNA”, which are genetic molecules that regulate the functioning of cells, organs and tissues. Trauma alters these “molecular directors,” and the defect is transmitted to progeny through gametes; in summary, these are short sequences with which the instructions for building proteins are transmitted but which also preserve the memory of traumatic events. Finally, from a neuropsychological point of view, recent studies [9-12] have demonstrated that trauma can alter some structures (and consequence certain brain functions, especially in the areas of the prefrontal cortex, the anterior cingulate cortex, the amygdala, the anterior part of the frontal lobe, all areas that involve rational thinking, problem-solving, and personality expression in various activities, planning, empathy and moderation in social behavior. An interesting theory still to be explored also suggests the involvement of the cerebellum in experiences of inadequate attachment and dysfunctional coping style [13].

When the traumatic event intervenes in the early years of life or negatively impacts the role of the subject’s reference figures because it is provoked by them or because they are victims of it, then the issue of childhood attachment comes into play. The author of the studies on “attachment theory, maternal bonding, and the consequences of deprivation of maternal care, is John Bowlby, who modified the current view that maternal bonding was based on hunger and nurture, according to a concept of interdependence [2,14]. Bowlby, through his studies, identified 5 specific stages [15]: a) I (0-3 months) or the pre-attachment, which consists of the implementation of spatial orientation (turning the head) and signaling behaviors (smiling, crying, leaving), by which the infant while recognizing the human figure when it appears in his field of vision does not specifically discriminate and recognize people; b) II (3-6 months) or the attachment information, in which the infant begins to distinguish between caring figures and occasional ones, showing this with increasingly obvious and marked behaviors (smiling); c) III (7-8 months) or anguish, in which he perceives this when a physical detachment from his caregiver figure is generated; d) IV (8-24 months) or true attachment, in which the true affective bond is created; e) V (over 24 months) or bond formation, in which the infant’s exploration becomes constant, even in maintaining external. However, she was Mary Ainsworth, Bowlby’s assistant, who made an important contribution by elaborating through the experimental situation called the “strange situation” the theory behind the Adult Attachment Interview, a psychometric instrument that can identify the 4 patterns of childhood attachment (secure, insecure-avoidant, insecure-ambivalent, disorganized-disoriented) and assess the different attachment behaviors of children in response to separation from their mother [16-23]. In particular [2,22-24], the following table, the details individual attachments (Table 1).

Studies in the field have shown a correlation between secure attachment and positive affectivity, with excellent problem-solving skills and self-confidence and better adjustment, especially in the early years of life [25]; conversely, insecure and disorganized patterns constitute a context of less developmental adaptation for the child, although there is little correlation between insecure attachment and psychopathological outcomes at preschool and school age, except for high psychosocial risk samples (extreme poverty, single parent, disrupted family context, psychogenic factors such as maternal depression and psychopathologies) that facilitate or predispose negatively [26]. On the point, several variables may affect dysfunctional patterns of personality, and therefore it is not easy to state with certainty the exact correlation, except to the extent of maladaptive characteristics such as peer/peer conflict, mood states, aggression and impulsivity [27,28]; other studies [29] associate maternal depression, associated with insecure-disorganized attachment, with hostile and externalizing behaviors in school age, while associated with insecure-avoidant attachment [30] would result in internalizing symptoms. In adults, however, studies would correlate ambivalent attachment with anxiety disorders [31] while disorganized attachment with psychotic symptoms [32-34], according to the international nosography of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of mental disorders - DSM-5-TR [35], which distinguishes psychopathological forms at all developmental stages [2,36-41].

The concepts of “facilitating factor” and “predisposing factor” in psychopathology, in the literature, are not unambiguous, and classifications in this regard are more indicative than exhaustive. This is also why, to date, it is challenging to state that a specific trauma or a specific dysfunctional attachment can always lead to a specific psychopathological disorder, as these other factors, under consideration here, may play a specific and not yet clear role [2,42,43]. Several authors have tried their hand at defining these 2 concepts, and for simplicity, in the following table (Table 2), they are given in schematic form; the theoretical basis of the present study is based on them.

Aim

A study was conducted, with a small sample, to test whether there could be a correlation between the presence of specific childhood trauma, with or without dysfunctional attachment, and one or more psychopathological personality tendencies, in the pediatric population investigated (primary outcome), and whether there may be a correlation between childhood trauma not properly processed and emotional intelligence (secondary outcome). The purpose of the present discussion is to try to determine whether, in the present state of scientific knowledge, it is possible to argue that certain unprocessed trauma factors can interfere with the healthy psychophysical development of the subject, up to and including true psychopathological forms.

Materials and methods

Study design

Investigation of personality profile, using the Perrotta Integrative Clinical Interviews (PICI-3) and the “Perrotta Human Emotions Questionnaire” (PHE-Q) to investigate emotional intelligence, compared with the Separation Anxiety Test (SAT) and clinical interview outcomes, investigating possible predisposing and facilitating factors.

Materials and methods

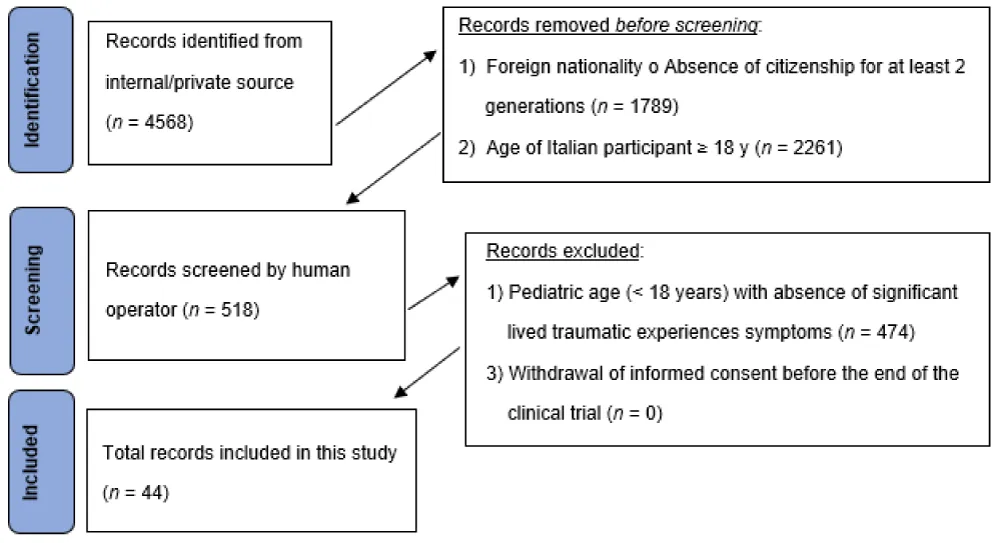

The author searched PubMed from January 2005 to March 2024 for systematic reviews, meta-analyses, clinical trials, and randomized controlled trials, using “attachment style AND trauma”, selecting 35 eligibility results. To have a greater and complete overview of the topic, ultimately selecting a total of 9 studies, still adding 47 more reviews to be able to argue the elaborated content (to more easily contextualize definitions and clinical-diagnostic profiles), for an overall total of 56 results. Simple reviews, opinion contributions, or publications in popular volumes were excluded because they were not relevant or redundant for this work. The search was not limited to English-language papers (Figure 1).

The present research is marked by the method of clinical analysis by direct interview (to obtain the history and personal history) and administration of 3 questionnaires: the “Separation Anxiety Test” (SAT), the “Perrotta Integrative Clinical Interviews”, version C-3 (PICI-C-3), and the “Perrotta Human Emotions Questionnaire” (PHE-Q). Specifically: a) the SAT studies one’s pattern of attachment in a developmental population by administering 12 tablets, in about 30 minutes [44]; b) the PICI-C-3 studies functional and dysfunctional personality traits in the pediatric population aged 8 to 17 years, using a battery of integrated questionnaires, according to a specific model, with administration in about 45 minutes [45]; c) the PHE-Q investigates subjective emotional intelligence in 78 items, with multiple responses, to evaluate the perceptual-emotional state, emotional understanding, emotional representation, emotional management and emotional relationship [46]. The questionnaires used are all validated, as reported in the references.

Setting and participants

The selected population was divided into 2 groups: the first (clinical group, CG) and the second (control group, CG). Inclusive criteria for CG are: 1) Age 8-17 years old; 2) Italian nationality or citizenship for at least 2 generations; and 3) narrative of one or more unresolved youthful traumatic experiences (occurring by the time they reached the age of majority, 18 years old). Exclusive criteria for CG are: 1) Age < 8 years and ≥ 18 years old; 2) foreign nationality or Italian nationality for less than 2 generations; 3) Absence of unresolved youth traumatic experiences. The sample of the CG is 44 units. All individuals with the same characteristics but with the absence of youthful traumatic experiences, regardless of their resolution, were included in the CG. For organizational reasons, Cg’s sample is also 44 units, comparable to each other in age and gender (Figure 2).

Taking into account the 2020-2022 pandemic period and the different geographical residences of the patients, it was preferred to carry out the clinical interview and administration of the questionnaires via the online video calling platforms Skype and WhatsApp. This research work was conducted from June 2021 to February 2024. As per the informed consent and data processing, all participants were guaranteed anonymity, and compliance with the ethical requirements of the Declaration of Helsinki. It was not necessary to request an opinion from the local Ethics Committee as the patients come from a private catchment area and the data are retrospective. The research is unfunded and free from conflicts of interest. The sample of the selected population is composed of 44 participants (16/males, 28/females) per group in equal measure, to carry out statistical case-controls, aged between 8 and 17 years (M: 12.9; SD: 3.1) for the entire study. The drop-out rate was 0/88 (0.0%) (Table 3).

Results

Once the population sample was selected and the subjects selected in both groups were standardized to guarantee the subsequent statistical analysis of the case controls, matched by age and sexual gender, the clinical interviews were carried out to compile the medical history and the patient card with the information necessary to be able to compare the data with the results of the questionnaires.

During the clinical interview, the therapist took note of the personal and family clinical history, sexual gender, age, type of childhood trauma not processed correctly (not treated in psychotherapy or through psychopharmacological administration), the presence of an addiction to substances or behaviour, the presence of inappropriate sexual behaviour, aggression, impulsivity, hyperactivity, distractibility, educational difficulties and socio-relational difficulties (Table 4), correlating them individually and in a series of multiple regressions with the data of the 3 questionnaires, the SAT for attachment, the PICI-C-3 for identifying the dysfunctional personality profile and the PHEQ to study emotional intelligence. In the following table, the descriptive details of possible childhood traumas are not processed correctly. It was not possible to integrate the study with health data on the genetic investigation, as none of the selected subjects had this information available.

By re-elaborating these values and choosing the variables, according to a grouping logic, it emerges that age, alone, is not in itself a greater or lesser risk factor but the dysfunctional weight could be determined by the impact of other factors or other conditions, such as the duration of exposure to the trauma, the repetitiveness of the negative effects of the trauma, the depth of suffering suffered following the traumatizing event, any behavioral reinforcements and the presence of traumatizing contributory causes (Figure 3).

The non-parametric statistical analysis performed (Chi-square or χ²) shows a clear significance (p < 0.05) on all tested variables, excluding gender (p = 1.000), age (p = 1.000), addictions, dysfunctional neurotic personality (p = 0.379) and in the average (p = 0.218) and above average (p = 0.743) forms of emotional intelligence, between the clinical and control groups (Table 5).

By carrying out the ANOVA statistical analysis, 3 different regression models are obtained with different degrees of robustness, if the variables with the highest significance (nos. 3, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22 and 23) are compared with the 3 variables referring to the 3 psychometric tests used in the research (n. 24 for the SAT, n. 29 for the PICI-C-3 and n. 34 for the PHEQ), keeping the collinearity (VIF) lower than 5.0. In the first case, we obtain a model that has an R-squared adjusted to 0.672 and p = 0.000, in the second case we obtain 0.452 with p = 0.000, and in the third case 0.069 with p = 0.099 (Table 6).

By carrying out the statistical analysis T-test for paired data, the statistical significance between CG and Cg is confirmed, comparing the patients by pairing the data by age (8-17 years) and sexual gender (male/female), with correlation values that are all higher than 0.500 (Table 7).

Discussion

The present research is trying, primarily, to answer the question of whether or not there is a possible correlation between the presence of specific unprocessed childhood traumas, with or without dysfunctional attachment, and one or more psychopathological tendencies of the personality, in the pediatric population investigated, and secondly, whether there is a possible correlation between the existence of traumas not processed correctly and subjective emotional intelligence. To answer these questions and satisfy the purpose of the research (to determine whether, in the current state of scientific knowledge, it is possible to maintain that some unprocessed traumatic factors are capable of interfering with the healthy psychophysical development of the subject, to the point of arriving at real own psychopathological pathologies) 2 groups were compared, one clinical and one control, and the research data were analyzed using statistics, which revealed significantly more alarming results than recent studies on the subject [46-49].

The first statistical confirmation is related to the frequency of comparisons between the two groups and about sexual gender. From here, it emerges that there are significant differences between the two groups, which reflect the general tendency of the data to represent a marked dysfunctionality following the presence of a childhood trauma not processed correctly, but also that these differences weaken (but do not disappear) when comparing clinical patients with control patients in certain variables. 11, 13, 14, 18, 20, 21, and 22, demonstrating that childhood trauma not processed correctly may not be the only cause of psychological dysfunction in developmental age; this conclusion is more evident with variable n. 16 in the female control group, where the score is even higher than that of the male (but not female) clinical group, which appears to be the highest among all, demonstrating that sexual behaviors in women could be more easily influenced by trauma than by men. Regarding attachment style, the general trend shows that an incorrectly processed childhood trauma can influence the style, but also that the insecure-avoidant style may not necessarily be the consequence of a consciously present childhood trauma. About the dysfunctional personality profile, the data confirm that the presence of childhood trauma not processed correctly is always correlated with a psychopathological personality profile, but may not be the only cause of this tendency, as in the control group there are still There are subjects who, despite not narrating traumatic childhood episodes that have not been processed correctly, have a dysfunctional profile that tends to be more neurotic and dramatic, while in the clinical group, there is a significant tendency towards dramatic and psychotic profiles. Finally, about emotional intelligence, the data collected show a truly alarming situation: almost all of the population sample (80/88, 91%), both clinical and control, presents levels lower than average, and only one a minimal part (9/88, 9%) has average or slightly higher values, confirming that it is not only childhood trauma that is not processed correctly that is the cause of a low level of emotional intelligence but there are other factors capable of generate this distortion, such as the education received, educational stimuli, maturation prospects, one’s neuropsychological inclinations and an adequate socio-family environment. No significant difference, however, emerges about the age of onset of the traumatic event, probably because it is not only age in itself that matters but other circumstances, such as the duration of exposure to the trauma, the repetitiveness of the negative effects of the trauma, the depth of suffering suffered following the traumatizing event, any behavioral reinforcements that have occurred over time and the presence of other traumatizing causes. Data was perfectly confirmed also by the statistical findings relating to case controls.

The second statistical finding is related to the non-parametric comparisons, which confirm what has been said so far, especially about gender, age, addictions, dysfunctional neurotic personality, and average and above-average forms of emotional intelligence. In particular, variables n. 14, 15, 31, 36, and 37 could be influenced not only by childhood trauma not being processed correctly but also by other factors that would act as contributing causes, such as educational style, behavioral reinforcement, socio-environmental stimuli, and subjective neuropsychological tendencies.

The third statistical finding is related to the regression models, which, on certain indicators, demonstrate that childhood trauma not processed correctly impacts the attachment style and personality profile, but in a weaker manner on emotional intelligence (which only seems to be conditioned but not predisposed in a pejorative sense).

In conclusion, it, therefore, appears completely clear that childhood trauma that is not processed correctly can be considered a factor that predisposes to the onset of a psychopathological personality disorder, but alone it is not capable of completing the dysfunctional operation, and for this requires other factors, predisposing and/or facilitating, such as the duration of exposure to the trauma, the repetitiveness of the negative effects of the trauma, the depth of the suffering suffered following the traumatizing event, any behavioral reinforcements that have occurred over time and the presence of other traumatizing causes such as psychophysical violence (with or without sexual intent), genetic predisposition and familiarity with certain psychopathologies, extreme economic poverty, the unfavorable socio-environmental and cultural context and difficulties in settling in.

For these reasons, a correct psychotherapeutic approach to childhood trauma that is not processed correctly, right from the first symptomatic manifestations, can favor the functional recovery of the patient, disinvesting in the chronification of the problem before it is able, in the presence of other contributing causes, to become a toxic splinter for the internal stability of the subject [56].

Limitations and prospects

This research work presents some limitations in the study design, which could partially affect the results. In particular, the genetic and familial predisposition of psychopathologies is not taken into account, as the data in possession are not complete from this specific investigation, and therefore, the type of study is retrospective. Furthermore, the population sample is small and therefore needs to be expanded to confirm the results, which, however, appear interesting, especially about the need for early psychotherapeutic intervention in the presence of childhood trauma and the central role of socio-environmental education and culture to avoid harming the personality profile. This first work serves to lay the foundations for a more in-depth investigation, based on the stimuli already found. Future studies will be focused on more widespread data collection, on the expansion of the quantitative sample of the population to be selected, and on the specific dysfunctional weight of the individual, which predisposes and favors psychopathology.

Conclusion

Unresolved childhood trauma can be considered a factor that predisposes to the onset of a psychopathological personality disorder, but alone it is not able to complete the dysfunctional operation, as it requires other predisposing and/or facilitating factors, such as duration of exposure to the trauma, the repetitiveness of the negative effects of the trauma, the depth of suffering suffered following the traumatizing event, any behavioral reinforcements that have occurred over time and the presence of other traumatizing causes, such as psychophysical violence (with or without sexual purpose), genetic predisposition and familiarity with some psychopathologies, extreme economic poverty, the unfavorable socio-environmental and cultural context and difficulties in settling in. A correct psychotherapeutic approach to childhood trauma, right from the first symptomatic manifestations, can promote functional recovery before the problem becomes chronic.

Ethics approval and consent to partecipate

This study was waived for ethical review and approval because all participants were assured compliance with the ethical requirements of the Charter of Human Rights, the Declaration of Helsinki in its most recent version, the Oviedo Convention, the guidelines of the National Bioethics Committee, the standards of “Good Clinical Practice” (GCP) in the most recent version, the relevant national and international ethical codes, as well as the fundamental principles of state law and international laws according to the updated guidelines on observational studies and clinical trial studies. For patients under the age of 18 years, specific permission to participate was requested by stipulation of data processing and computer consent from both parents or legal guardians. Pursuant to Legislative Decree No. 52/2019 and Law No. 3/2018, this research does not require the prior opinion of an ethics committee, in implementation of Regulation (EU) No. 536/2014 and in accordance with Regulation (EU) 2017/745, the Declaration of Helsinki and the Oviedo Convention, since the scientific research contained in the manuscript: (a) does not concern new or already marketed drugs or medical devices; (b) does not involve the administration of a new or already marketed drug or medical device; (c) does not have commercial purposes; (d) is not sponsored or funded; (e) participants have signed the informed consent and data processing, in compliance with applicable national and EU regulations; (f) refers to non-interventional and observational-comparative diagnostic topics; (g) the population sample was collected at a date before the start of this study and is part of a private and non-public database.

CoNot sent for publication

Study participants, by signing informed consent and data processing, consented to the publication of data in anonymous and aggregate form. Subjects who gave regular informed consent agreements were recruited; moreover, these subjects requested and obtained from Giulio Perrotta, as the sole examiner and project manager, not to meet the other study collaborators, thus remaining completely anonymous. The authors, in compliance with applicable regulations, consent to the publication of the contents of this clinical study.

Availability of data and material

The subjects who participated in the study requested and obtained that Giulio Perrotta be the sole examiner during the therapeutic sessions and that all other authors be aware of the participants’ data in an exclusively anonymous form. Authors make themselves available, by formal request, to be evaluated on a case-by-case basis, to disclose research data and materials, in aggregate and anonymous form only, subject to applicable regulations and the informed consent and data processing signed by participants.

Authors’ contribution

Giulio Perrotta designed, developed, and validated the questionnaire and drafted the manuscript. Stefano Eleuteri supervised the manuscript and statistical analysis.

- Gabbard GO. Introduction to psychodynamic psychotherapy. 3rd ed. Milan: Raffaello Cortina Publisher. 2018.

- Perrotta G. Dynamic Psychology. 1st ed. Turin: Luxco Publishing House; 2019.

- Perrotta G. Psychological trauma: definition, clinical contexts, neural correlations and therapeutic approaches. Curr Res Psychiatry Brain Disord. 2020;1(CRPBD-100006):1–6. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/344428587_Psychological_Trauma_Definition_Clinical_Contexts_Neural_Correlations_and_Therapeutic_Approaches_Recent_Discoveries

- Perrotta G, Basiletti V. The emotional intelligence (EI) and “Perrotta Human Emotions – Questionnaire – 1” (PHE-Q-1): development, regulation and validation of a new psychometric instrument. Arch Community Med Public Health. 2023;9(4):055–063. Available from: https://dx.doi.org/10.17352/2455-5479.000203

- Dickson DA, Paulus JK, Mensah V, Lem J, Saavedra-Rodriguez L, Gentry A, et al. Reduced levels of miRNAs 449 and 34 in sperm of mice and men exposed to early life stress. Transl Psychiatry. 2018;8(1):101. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-018-0146-2

- Gapp K, Bohacek J, Grossmann J, Brunner AM, Manuella F, Nanni P, et al. Potential of environmental enrichment to prevent transgenerational effects of paternal trauma. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016;41(11):2749–2758. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2016.87

- Gapp K, Jawaid A, Sarkies P, Bohacek J, Pelczar P, Prados J, et al. Implication of sperm RNAs in transgenerational inheritance of the effects of early trauma in mice. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17(5):667–669. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.3695

- Gapp K, Soldado-Magraner S, Bohacek J, Bohacek J, Vernaz G, Shu H, et al. Early life stress in fathers improves behavioural flexibility in their offspring. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5466. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms6466

- Chiocchetti AG, Yousaf A, Waltes R, Bernhard A, Martinelli A, Ackermann K, et al. The methylome in females with adolescent conduct disorder: neural pathomechanisms and environmental risk factors. PLoS One. 2022;17(1):e0261691. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0261691

- Mishra J, Sagar R, Parveen S, Kumaran S, Modi K, Maric V, et al. Closed-loop digital meditation for neurocognitive and behavioral development in adolescents with childhood neglect. Transl Psychiatry. 2020;10(1):153. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-020-0820-z

- Santarnecchi E, Bossini L, Vatti G, Fagiolini A, La Porta P, Di Lorenzo G, et al. Psychological and brain connectivity changes following trauma-focused CBT and EMDR treatment in single-episode PTSD patients. Front Psychol. 2019;10:129. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00129

- Heany SJ, Groenewold NA, Uhlmann A, Dalvie S, Stein DJ, Brooks SJ. The neural correlates of Childhood Trauma Questionnaire scores in adults: a meta-analysis and review of functional magnetic resonance imaging studies. Dev Psychopathol. 2018;30(4):1475–1485. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579417001717

- Borsato T. The cerebellum and traumatic memories: a neuro-functional hypothesis on post-traumatic stress disorder and EMDR therapy [doctoral thesis]. Milan: University of Milan Bicocca; 2015. Available from: https://boa.unimib.it/retrieve/e39773b2-fb06-35a3-e053-3a05fe0aac26/phd_unimib_760794.pdf

- Suomi SJ, Leroy HA. In memoriam: Harry F. Harlow (1905–1981). Am J Primatol. 1982;2:319–342. Available from: https://www.academia.edu/19008017/In_memoriam_Harry_F_Harlow_1905_1981_

- Bowlby J. Una base sicura: applicazioni cliniche della teoria dell'attaccamento. 3rd ed. Milano: Raffaello Cortina Editore; 1989. Available from: https://www.raffaellocortina.it/scheda-libro/john-bowlby/una-base-sicura-9788870780888-130.html

- Dazzi N, Zavattini GC. Adult Attachment Interview: Clinical applications. 1st ed. Milan: Raffaello Cortina Editore; 2010.

- Lieberman AF. Toddlers' internalization of maternal attributions as a factor in quality of attachment. In: Attachment and psychopathology. New York: Guilford Press; 1997;277–292. Available from: https://www.scribd.com/document/190794373/Lieberman-A-F-1999-Negative-Maternal-Attributions

- Johnson-Laird PN. Mental models. 1st ed. Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press. 1983;179–187. Available from: https://www.scirp.org/reference/referencespapers?referenceid=1790686

- George C, Kaplan N, Main M. Adult Attachment Interview. 1st ed. Berkeley (CA): University of California Press; 1985. Available from: https://www.scirp.org/reference/referencespapers?referenceid=557265

- Zeanah CH, Keener MA, Anders TF. Adolescent mothers' prenatal fantasies and working models of their infants. Psychiatry. 1986;49(3):193–203. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1080/00332747.1986.11024321

- Main M, Kaplan N, Cassidy J. Security in infancy, childhood, and adulthood: a move to the level of representation. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev. 1985;50:66–104. Available from: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3333827

- Ainsworth M, Blehar M, Waters E, Wall S. Patterns of attachment. 1st ed. New York: Hillsdale Press; 1978. Available from: https://mindsplain.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Ainsworth-Patterns-of-Attachment.pdf

- Ainsworth M, Bowlby J. Child care and the growth of love. 1st ed. London: Penguin Books; 1965.

- Bartholomew K, Horowitz LM. Attachment styles among young adults: a test of a four-category model. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1991;61(2):226–244. Available from: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1991-33075-001

- Kochanska G. Emotional development in children with different attachment histories: the first three years. Child Dev. 2001;72(2):474–490. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00291

- Lyons-Ruth K, Connell DB, Grunebaum HU. Infants at social risk: maternal depression and family support services as mediators of infant development and security of attachment. Child Dev. 1990;61(1):85–98. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02762.x

- Erikson MF, Egeland B, Sroufe LA. The relationship of quality of attachment and behaviour problems in preschool in a risk sample. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev. 1985;209(1):147–186. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/4069126/

- Egeland B, Sroufe LA. Developmental sequelae of maltreatment in infancy. New Dir Child Dev. 1981;(11):77–92. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1981. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/cd.23219811106

- Lyons-Ruth K. Infants at social risk: relationships among infant maltreatment, maternal behavior, and infant attachment behavior. Dev Psychol. 1987;23(2):223–232. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.23.2.223

- Greenberg MT, Speltz ML, De Klyen M. The role of attachment in the early development of disruptive behavior problems. Dev Psychopathol. 1993;5(1–2):191–213. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1017/S095457940000434X

- Warren SL, Huston L, Egeland B, Sroufe LA. Child and adolescent anxiety disorders and early attachment. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36(5):637–644. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199705000-00014

- Carlson EA. A prospective longitudinal study of disorganized/disoriented attachment. Child Dev. 1998;69(4):1107–1128. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9768489/

- Van IJzendoorn MH, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ. Intergenerational transmission of attachment: a move to the contextual level. In: Atkinson L, Zucker KJ, editors. Attachment and psychopathology. New York: Guilford Press; 1997;135–170. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/28639629_Intergenerational_transmission_of_attachment_A_move_to_the_contextual_level

- Fonagy P, Leigh T, Steele M, Steele H, Kennedy R, Mattoon G, et al. The relation of attachment status, psychiatric classification, and response to psychotherapy. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996;64(1):22–31. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-006x.64.1.22

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5-TR. 5th ed. Washington (DC): American Psychiatric Publishing; 2022. Available from: https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/dsm

- Ellis EE, Saadabadi A. Reactive attachment disorder [Internet]. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 [cited 2025 Dec 15]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537155/

- Atkinson L. Reactive attachment disorder and attachment theory from infancy to adolescence: review, integration, and expansion. Attach Hum Dev. 2019;21(2):205–217. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2018.1499214

- Hiebler-Ragger M, Unterrainer HF. The role of attachment in poly-drug use disorder: an overview of the literature, recent findings and clinical implications. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:579. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00579

- Huang YC, Lee Y, Lin PY, Hung CF, Lee CY, Wang LJ. Anxiety comorbidities in patients with major depressive disorder: the role of attachment. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2019;23(4):286–292. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1080/13651501.2019.1638941

- Petrowski K. Implicit attachment schemas and therapy outcome for panic disorder treated with manualized confrontation therapy. Psychopathology. 2019;52(3):184–190. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1159/000496500

- Vega H, Cole K, Hill K. Interventions for children with reactive attachment disorder. Nursing. 2019;49(6):50–55. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1097/01.nurse.0000554615.92598.b2

- Lo Bello V. The psychopathological boundary between deviance and criminality: clinical approach [bachelor’s thesis]. Messina: University of Messina; 2023. Available from: https://morethesis.unimore.it/theses/browse/by_tipo/LM5.html

- Perrotta G, Fabiano G, Posta F. The psychopathological evolution of “behavior and conduct disorder in childhood”: deviant and criminal traits in preadolescence and adolescence. A review. Open J Pediatr Child Health. 2023;8(1):045–059. Available from: https://www.healthdisgroup.us/articles/OJPCH-8-151.php

- Attili G. Separation anxiety and the measurement of normal and pathological attachment. 1st ed. Milan: Unicopli Editore; 2001.

- Perrotta G. Perrotta integrative clinical interviews-3 (PICI-3): development, regulation, updation, and validation of the psychometric instrument for the identification of functional and dysfunctional personality traits and diagnosis of psychopathological disorders, for children, preadolescents, adolescents, adults, and elders. Ibrain. 2024:1–18. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/ibra.12148

- Gleeson A, Curran D, Reeves R, Dorahy MJ, Hanna D. A meta-analytic review of the relationship between attachment styles and posttraumatic growth. J Clin Psychol. 2021;77(7):1521–1536. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.23156

- Lecomte T. Acceptance and commitment therapy for psychosis and trauma: investigating links between trauma severity, attachment, and outcome. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2019;47(2):230–243. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465818000413

- Lo CKL, Chan KL, Ip P. Insecure adult attachment and child maltreatment: a meta-analysis. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2019;20(5):706–719. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838017730579

- Woodhouse S, Ayers S, Field AP. The relationship between adult attachment style and post-traumatic stress symptoms: a meta-analysis. J Anxiety Disord. 2015;35:103–117. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2015.07.002

- Farrington DP, Barnes GC, Lambert S. The concentration of offending in families. Legal Criminol Psychol. 1996;1(1):47–63. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1006/jado.2001.0424

- Farrington DP. Juvenile delinquency. In: Coleman JC, editor. The school years. 2nd ed. Routledge Press; 1992;123–63. Available from: https://www.scirp.org/reference/referencespapers?referenceid=1620951

- Farrington DP. Early predictors of adolescent aggression and adult violence. Violence Vict. 1989;4(2):79–100. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2487131/

- Jaffee S, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Belsky J, Silva P. Why are children born to teen mothers at risk for adverse outcomes in young adulthood? Results from a 20-year longitudinal study. Dev Psychopathol. 2001;13(2):377–397. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579401002103

- Lipsey MW, Derzon JH. Predictors of violent or serious delinquency in adolescence and early adulthood: a synthesis of longitudinal research. In: Loeber R, Farrington DP, editors. Serious and violent juvenile offenders: risk factors and successful interventions. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publications. 1998;86–105. Available from: https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452243740.n6

- Elliott DS, Menard S. Delinquent friends and delinquent behavior: temporal and developmental patterns. In: Hawkins JD, editor. Delinquency and crime: current theories. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1996;28–67. Available from: https://scirp.org/reference/referencespapers?referenceid=1795931

- Mrazek PJ, Haggerty RJ. Reducing risks for mental disorders: frontiers for preventive intervention research. 1st ed. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 1994. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25144015/

Article Alerts

Subscribe to our articles alerts and stay tuned.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Save to Mendeley

Save to Mendeley