False-Positive Focused Assessment with Sonography in Trauma (FAST) Exam in a Pediatric Trauma Patient Highlights Concerns for the Operational Environment: A Case Report

1Department of Emergency Medicine, Carl R. Darnall Army Medical Center, 36065 Santa Fe Ave, Fort Cavazos, TX 76544, USA

2Dell Children’s Medical Center, 4900 Mueller Blvd, Austin, TX 78723, USA

3Arizona College of Osteopathic Medicine, 19555 N 59th Ave, Glendale, AZ 85308, USA

4Special Operations Forces to School of Medicine, 1312 Sunswept Cir, Raleigh, NC 27603, USA

5West Virginia School of Medicine, 64 Medical Center Drive, Morgantown, WV, USA

667th Forward Resuscitative Surgical Detachment, Rhine Ordnance Barracks, Building 300, 67661, Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany

7Advanced Emergency Medicine Ultrasound Fellowship Director, Department of Emergency Medicine, Carl R. Darnall Army Medical Center, 36065 Santa Fe Ave, Fort Cavazos, TX 76544, USA

Author and article information

Cite this as

Alexandri M, Soules AK, Wolterstorff CS, Mitchell CA, Hill GJ, Dodson E, et al. False-Positive Focused Assessment with Sonography in Trauma (FAST) Exam in a Pediatric Trauma Patient Highlights Concerns for the Operational Environment: A Case Report. Open J Trauma. 2025;9(1):027-031. Available from: 10.17352/ojt.000050

Copyright License

© 2025 Alexandri M, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.Abstract

Introduction: The Focused Assessment with Sonography in Trauma (FAST) ultrasound exam is a critical tool used by medical providers in deployed settings to identify life-threating injuries and inform triage decisions. Its application to pediatric patients, however, remains underexplored and faces obstacles in austere, combat environments. Diagnostic inaccuracies using FAST in this context may result in unnecessary evacuations or missed injuries, straining battlefield resources and operational priorities.

Case presentation: A six-month old female presented to a military treatment facility Emergency Department after a blunt trauma injury and received a FAST exam that was interpreted as positive for intraperitoneal free fluid. Her AST was mildly elevated at 67. Subsequent CT scan of the abdomen was negative for intrabdominal injury.

Discussion: Pediatric FAST exams present unique questions which have not been considered adequately in the military medical literature. Although the FAST exam is not intended to be used in isolation, deployed medical providers have limited access to ancillary testing that could otherwise inform interpretation of a pediatric FAST exam. The relative rarity of pediatric trauma in the deployed environment heightens the risk of false positives and negatives. As demonstrated by the case presentation, even with ancillary testing and an experienced operator, the FAST exam in pediatric patients can yield false positives that could strain scarce resources in austere settings.

Conclusion: With respect to the FAST exam in pediatric trauma patients, an urgent need exists for additional research, robust training, and a JTS CPG.

Background

The Joint Trauma System advises that “[o]ur deployed medical teams need to be prepared to care for injured children in the combat environment [1]”. The numbers bear out this admonition. According to an analysis of a Department of Defense Trauma Registry query by Schauer, et al. pediatric patients (those younger than 18 years of age) comprised 8% of prehospital trauma patients between 2007 and 2016 [2]. Naylor, et al. reported that an estimated 30% of pediatric trauma patients required medical evacuation from point of injury to a surgical facility [3]. At one forward resuscitative surgical detachment, almost 40% of the patients were pediatric [4].

As high intensity combat, irregular warfare, and large-scale combat operations proliferate in densely-populated, urban environments, the number of pediatric trauma patients receiving care from military medical clinicians is likely to increase. For example, estimates from the conflict in Gaza include 25,000 injured children in a 15-month period [5], as compared with almost 3,500 children in a nine-year period spanning the Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts [2].

Outside the combat environment, most children presenting with blunt trauma are less likely to receive focused assessment with sonography in trauma (FAST) exams in their primary surveys when compared to adults [6-8]. With respect to those who do, studies show mixed results. Some study results support the conclusion that the FAST exam does not change management [6,9], while others conclude the opposite [10]. As for patient-oriented outcomes, FAST exam results may not decrease abdominal computed tomography (CT) scans in children [9], and their impact on decision making about surgical intervention remains nuanced [11].

Two meta-analyses conducted in the past two decades both concluded that, although the FAST exam is specific for intra-abdominal injury (IAI) in pediatric patients, it is not sensitive [8,12], a finding consistent across the literature [6,7,13]. As a result, the context for the FAST exam, including vital signs, physical exam, laboratory results (specifically alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) [14]), and operator training and experience, is integral to its use [7,11,12,15,16].

That said, ALT and AST results are unlikely to be available to guide decision-making between the point-of-injury and a Role 2. Similarly, operator training and experience performing FAST exams on pediatric trauma patients is likely to be limited in both the Role 1 and Role 2 echelons of care. Diagnostic inaccuracies using FAST in this context may result in unnecessary evacuations, missed injuries, and inappropriate blood transfusions, resulting in misallocation of battlefield resources and misalignment of operational priorities. To highlight the need for additional research and training on this procedure, we present the case of a false-positive FAST exam performed under optimal circumstances, as well as our analysis of a literature review.

Case presentation

The patient was a 6-month-old female with no past medical history presenting with both parents to the Emergency Department of a military treatment facility following a blunt trauma with an unclear history. She had fallen approximately two feet onto a hardwood floor. She cried immediately, was consolable and had been tolerating oral intake following the fall. The patient’s mother denied loss of consciousness, altered mental status, or vomiting, and the patient was alert on the primary and secondary surveys.

The patient’s vital signs were as follows: rectal temperature of 36.2 0C, heart rate of 137, respiratory rate of 24, blood pressure of 113/78, and a pulse oximetry of 100% on room air. The infant cried continuously, which limited the physical exam; nonetheless, she was found to have an atraumatic, normocephalic head, soft abdomen, and a non-focal neurological exam limited by her age and tears.

The patient’s WBC, hemoglobin, and hematocrit laboratory results were unremarkable. Her platelets were mildly elevated at 457 x 103/μL. The patient’s glucose was 114, electrolytes and BUN were unremarkable, creatinine was slightly elevated at 0.5, alkaline phosphatase and ALT were within normal limits, and AST was elevated at 67.

An X-ray “Babygram” of patient’s skeleton was unrevealing.

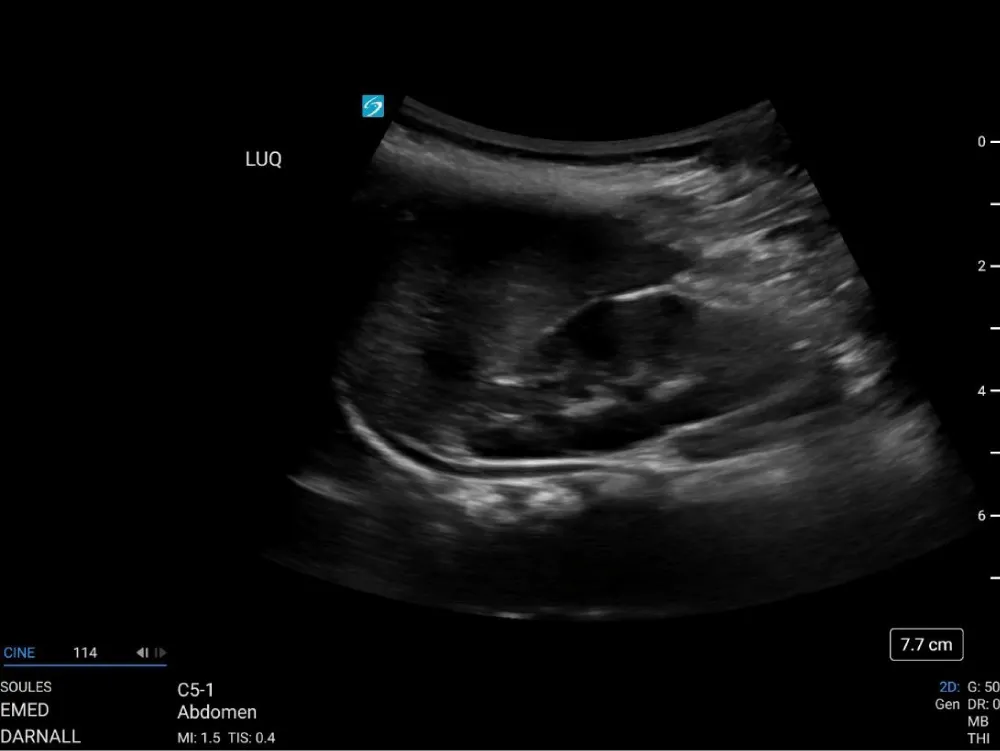

Because of questions surrounding the history of patient’s fall, the care team assessed the pre-test probability of IAI was sufficient to warrant imaging, so a point-of-care FAST exam was performed for diagnostic purposes using a Fujifilm Sonosite PX ultrasound system (Fujifilm Sonosite, Bothwell, WA) with a 1-5 MHz curvilinear probe on abdominal exam settings. The operator was an emergency medicine resident physician on an ultrasound rotation, supervised in the room by ultrasound fellowship faculty. The left upper quadrant window was significant for an anechoic stripe in the subdiaphragmatic area, concerning free fluid (Figure 1 and Video 1.) To assess whether the anechoic stripe was a blood vessel, color doppler was placed over it, with no indication of directional flow.

Video 1: Cine loop of the initial LUQ FAST view obtained on the Fujifilm Sonosite PX ultrasound system.

The patient’s abdominal exam was repeated, and it remained soft. Owing to patient’s crying, the exam was not a reliable indicator of pain, but no distension or guarding was appreciated.

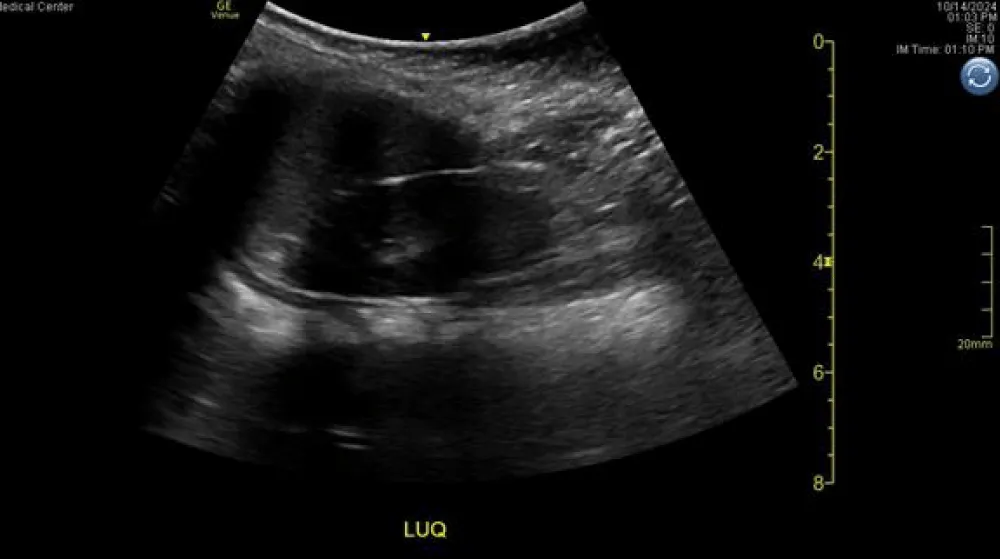

Hypothesizing that the anechoic stripe in the left upper quadrant might be an artifact resulting from image processing, as suggested by Baer Ellington, et al. [17] the point of care FAST exam was repeated by the ultrasound faculty member, an individual with more than a decade of experience, well over a thousand scans, and multiple sonography certifications, using a GE Venue ultrasound system (General Electric, Boston, MA) with a 1-5 MHz curvilinear probe and abdominal settings. The left upper quadrant window was again concerning for a subdiaphragmatic anechoic stripe (Figure 2 and Video 2).

Video 2: Cine loop of the repeat LUQ FAST examination obtained using the GE Venue ultrasound system.

Because of the duplicate point of care images concerning for fluid in the left upper quadrant FAST exam, additional imaging or repeat abdominal examination was warranted. The military treatment facility did not admit pediatric trauma patients, so the care team engaged in shared decision making with the patient’s parents, as to whether to transfer the patient or send her to CT. The patient’s parents, in conjunction with her care team, decided to perform a CT of patient’s abdomen and pelvis with IV contrast that was negative for intrabdominal fluid or any acute traumatic injury. She was discharged with recommended outpatient pediatrician follow-up. Six weeks later, her father reported that she was healthy and meeting her age-based benchmarks.

Discussion

Although additional research assessing use of the FAST exam on pediatric trauma patients treated by military medical clinicians in the deployed setting is necessary, the FAST exam has the potential to be a valuable adjunct to the care children receive in austere or combat environments. When making critical clinical decisions, including transfusion of blood products, surgical intervention, and medical evacuation, military medical clinicians in deployed settings need an understanding of which patients will benefit from scarce operational resources, and the FAST exam can help them.

That said, the clinicians must also develop an understanding of the limitations of the FAST exam. The evidence base for the pediatric FAST exam is still evolving, and indications for its use are still being refined. This includes answering the question of whether the pediatric FAST exam is indicated for hemodynamically stable children presenting after blunt abdominal trauma, both in the civilian and military contexts. Another limitation of the FAST exam arises when it is performed by less experienced operators, which is the common situation in most Role 1 care environments, as they are often staffed by junior physician assistants.

Operational use of the FAST exam in pediatric patients: medical evacuation and disposition

Importantly, the FAST exam is specific for pediatric IAI [6,7,12,13]. In hemodynamically stable children, a positive FAST exam indicates a need for abdominal CT scan [19], while in hemodynamically unstable pediatric blunt trauma patients, a positive FAST exam predicts the need for early surgical intervention [10,16]. In both such situations, medical evacuation from the point of injury may be justified, depending on the circumstances, including the rules of engagement, family preferences, and availability of assets.

Although the FAST exam is not sensitive in isolation, its use can nonetheless yield useful guidance about disposition. A negative FAST exam predicts successful non-operative management of pediatric trauma patients with liver or spleen IAI [18]. Likewise, in hemodynamically stable children, a negative physical exam combined with a negative FAST exam predicts non-operative management [11]. Delaying evacuation of pediatric trauma patients suspected to have blunt abdominal trauma who have negative FAST exams may be justified, especially since the FAST exam can be repeated in response to a child’s evolving condition, and medical evacuation can be initiated if the FAST exam becomes positive.

Operational use of the FAST exam in pediatric patients: lab values

Combining a FAST examination with other data points, like laboratory values for AST and ALT (which independently predict pediatric IAI [19]), also increases the exam’s sensitivity, specificity, and negative predictive value [14,20]. Sola, et al. conducted a retrospective review spanning a 17-year period of pediatric blunt abdominal trauma at a Level 1 trauma center and reported that the negative predictive value of FAST combined with transaminases was 96% [14]. They concluded that “FAST combined with elevated AST or ALT is an effective screening tool for IAI in children [14]”. Zeeshan, et al. confirmed these results: “combining FAST, [physical exam], and ALT and AST levels … significantly increased both the sensitivity and negative predictive value for screening pediatric blunt trauma patients with liver injury [20]”.

At present, ALT and AST laboratory results are not routinely available forward of a Role 2. Medical evacuation from point of injury to a Role 2 may be justified to screen pediatric blunt trauma patients for IAI in certain situations.

Operational use of the FAST exam in pediatric patients: training

In all events, additional training on pediatric FAST exam performance may be justified because the FAST exam is operator dependent [15,21,22], and practicing on adults does not necessarily prepare an operator to interpret a FAST exam properly in a child. While a positive FAST exam in an adult is most likely to show free fluid in the right upper quadrant, pediatric trauma patients with IAI and a positive FAST exam most often have fluid in their pelvis [10,15,16,23]. Facility obtaining the pelvic view on a pediatric FAST exam is therefore important, but one study found that the pelvic view was the one on which surgeons trained to perform the FAST exam felt least comfortable [18].

Pediatricians trained in emergency trauma response are infrequently present in military theaters of operations [2,3,24]. Even those with dedicated training in pediatric trauma care may not have seen a positive FAST exam in a pediatric patient, because the finding is rare [15]. “This underscores the importance of continued training and supervision for these exams …. It is possible that some pediatric and emergency medicine trainees may graduate without ever” being the operator on a positive FAST exam [15].

Operational use of the FAST exam in pediatric patients: risk of false positives and false negatives

False-positives, as well as false-negatives, are additional risks when FAST exams are performed in children. Perinephric fat, for example, may appear hypoechoic and can be mistaken for fluid [17,25]. Processing software on the ultrasound system may also play a role in altering the appearance of artifact in a way that is concerning for free fluid. Moreover, the handheld and portable ultrasound systems most likely to be found in the austere or combat environment may present different software processing challenges than found on the ultrasound systems most commonly used in Emergency Departments and the studies under review.

As demonstrated by our case report, false positives can occur with experienced operators in a context where the additional data points of physical exam and AST and ALT laboratory results are available. The treating physicians in our case had the benefit of multiple attending and resident physicians, two ultrasound systems, repeated physical exams, laboratory results, and shared decision-making with the patient’s parents in opting for an abdominal CT. Deployed medical clinicians will not enjoy that luxury, and allocation of operational resources will depend on their decisions.

Conclusion

This case underscores the critical need for additional research and training to ensure accurate pediatric FAST exam interpretation, thereby enhancing patient safety and supporting informed clinical decision-making far forward.

Declarations

Consent for publication: Written consent from the patient’s father was obtained.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this case report are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, Department of Defense, or US Government.

References

- Joint Trauma System, Clinical Practice Guideline: Prevention of Venous Thromboembolism. 2024. accessed May. 30, 2025. Available from: https://jts.health.mil/assets/docs/cpgs/Prevention_of_Venous_Thromboembolism_29_Mar_2024_ID36v1.1.pdf

- Schauer SG, April MD, Hill GJ, Naylor JF, Borgman MA, De Lorenzo RA. Prehospital Interventions Performed on Pediatric Trauma Patients in Iraq and Afghanistan. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2018;22(5):624-629. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1080/10903127.2018.1439130

- Naylor JF, April MD, Thronson EE, Hill GJ, Schauer SG. U.S. Military Medical Evacuation and Prehospital Care of Pediatric Trauma Casualties in Iraq and Afghanistan. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2020;24(2):265-272. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1080/10903127.2019.1626956

- Kocik VI, Borgman MA, April MD, Schauer SG. A scoping review of two decades of pediatric humanitarian care during wartime. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2023;95(2S Suppl 1):S170-S179. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1097/ta.0000000000004005

- Lederer, E. “Devastating toll for Gaza’s children: Over 13,000 killed and an estimated 25,000 injured, UN says.” AP News. 2025. last accessed Feb. 23, 2025. Available from: https://apnews.com/article/un-gaza-war-children-killed-malnutrition-israel-bef00a350a7fbe5a33dfb2c9883803ce

- Calder BW, Vogel AM, Zhang J, Mauldin PD, Huang EY, Savoie KB, et al. Focused assessment with sonography for trauma in children after blunt abdominal trauma: A multi-institutional analysis. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017;83(2):218-224. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1097/ta.0000000000001546

- Scaife ER, Rollins MD, Barnhart DC, Downey EC, Black RE, Meyers RL, et al. The role of focused abdominal sonography for trauma (FAST) in pediatric trauma evaluation. J Pediatr Surg. 2013;48(6):1377-83. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2013.03.038

- Holmes JF, Gladman A, Chang CH. Performance of abdominal ultrasonography in pediatric blunt trauma patients: a meta-analysis. J Pediatr Surg. 2007;42(9):1588-94. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2007.04.023

- Holmes JF, Kelley KM, Wootton-Gorges SL, Utter GH, Abramson LP, Rose JS, et al. Effect of Abdominal Ultrasound on Clinical Care, Outcomes, and Resource Use Among Children With Blunt Torso Trauma: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2017;317(22):2290-2296. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.6322

- Long MK, Vohra MK, Bonnette A, Parra PDV, Miller SK, Ayub E, et al. Focused assessment with sonography for trauma in predicting early surgical intervention in hemodynamically unstable children with blunt abdominal trauma. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2022;3(1):e12650. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/emp2.12650

- Tummers W, van Schuppen J, Langeveld H, Wilde J, Banderker E, van As A. Role of focused assessment with sonography for trauma as a screening tool for blunt abdominal trauma in young children after high energy trauma. S Afr J Surg. 2016;54(2):28-34. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28240501/

- Liang T, Roseman E, Gao M, Sinert R. The Utility of the Focused Assessment With Sonography in Trauma Examination in Pediatric Blunt Abdominal Trauma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2021;37(2):108-118. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1097/pec.0000000000001755

- Fox JC, Boysen M, Gharahbaghian L, Cusick S, Ahmed SS, Anderson CL, et al. Test characteristics of focused assessment of sonography for trauma for clinically significant abdominal free fluid in pediatric blunt abdominal trauma. Acad Emerg Med. 2011;18(5):477-82. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01071.x

- Sola JE, Cheung MC, Yang R, Koslow S, Lanuti E, Seaver C, et al. Pediatric FAST and elevated liver transaminases: An effective screening tool in blunt abdominal trauma. J Surg Res. 2009;157(1):103-7. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2009.03.058

- Riera A, Hayward H, Torres Silva C, Chen L. Reevaluation of FAST Sensitivity in Pediatric Blunt Abdominal Trauma Patients: Should We Redefine the Qualitative Threshold for Significant Hemoperitoneum? Pediatr Emerg Care. 2021;37(12):e1012-e1019. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1097/pec.0000000000001877

- Inci O, Altuncı YA, Can O, Akarca FK, Ersel M. The Efficiency of Focused Assessment with Sonography for Trauma in Pediatric Patients with Blunt Torso Trauma. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2024;17(1):8-13. Available from: https://doi.org/10.4103/jets.jets_137_22

- Baer Ellington A, Kuhn W, Lyon M. A Potential Pitfall of Using Focused Assessment With Sonography for Trauma in Pediatric Trauma. J Ultrasound Med. 2019;38(6):1637-1642. Available from: https://2024.sci-hub.se/7153/f9104ec573405fc5ef169d3a19a88738/baerellington2018.pdf

- McGaha P 2nd, Motghare P, Sarwar Z, Garcia NM, Lawson KA, Bhatia A, et al. Negative Focused Abdominal Sonography for Trauma examination predicts successful nonoperative management in pediatric solid organ injury: A prospective Arizona-Texas-Oklahoma-Memphis-Arkansas + Consortium study. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2019;86(1):86-91. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1097/ta.0000000000002074

- Holmes JF, Sokolove PE, Brant WE, Palchak MJ, Vance CW, Owings JT, et al. Identification of children with intra-abdominal injuries after blunt trauma. Ann Emerg Med. 2002;39(5):500-9. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1067/mem.2002.122900

- Zeeshan M, Hamidi M, O'Keeffe T, Hanna K, Kulvatunyou N, Tang A, et al. Pediatric Liver Injury: Physical Examination, Fast and Serum Transaminases Can Serve as a Guide. J Surg Res. 2019;242:151-156. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2019.04.021

- Heydari F, A, Kolahdouzan M. Diagnostic Accuracy of Focused Assessment with Sonography for Blunt Abdominal Trauma in Pediatric Patients Performed by Emergency Medicine Residents versus Radiology Residents. Adv J Emerg Med. 2018;2(3):e31. Available from: https://doi.org/10.22114/ajem.v0i0.89

- Moore C, Liu R. Not so FAST-let’s not abandon the pediatric focused assessment with sonography in trauma yet. J Thorac Dis. 2018;10(1):1-3. Available from: https://doi.org/10.21037/jtd.2017.12.37

- Brenkert TE, Adams C, Vieira RL, Rempell RG. Peritoneal fluid localization on FAST examination in the pediatric trauma patient. Am J Emerg Med. 2017;35(10):1497-1499. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2017.04.025

- Edwards MJ, Lustik M, Burnett MW, et al. Pediatric inpatient humanitarian care in combat: Iraq and Afghanistan 2002 to 2012. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;218(5):1018-23. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.12.050

- Fornari MJ, Lawson SL. Pediatric Blunt Abdominal Trauma and Point-of-Care Ultrasound. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2021;37(12):624-629. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1097/pec.0000000000002573

Article Alerts

Subscribe to our articles alerts and stay tuned.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Save to Mendeley

Save to Mendeley