Global Journal of Clinical Virology

Understanding EHV-1 and EHV-4: From Viral Structure to Epidemiological Impact

Pharmaceutical Sciences Research Center, 25016 Ali Mendjeli, Constantine, Algeria

Author and article information

Cite this as

Derbal S. Understanding EHV-1 and EHV-4: From Viral Structure to Epidemiological Impact. Glob J Clin Virol. 2025; 10(1): 007-015. Available from: 10.17352/gjcv.000016

Copyright License

© 2025 Derbal S. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.Several herpesviruses are capable of infecting equines, and these pathogens all have common structural, genetic, and biological characteristics. Notably, they exhibit similar viral organisation, undergo replication in distinct stages, and possess the ability to establish persistent infections. In horses, equine herpesvirus (EHV) transmission and excretion can occur by various routes, including direct contact with respiratory secretions, environmental contamination, or vertical transmission in certain cases. Protection against these infections relies on a complex immune response: humoral immunity helps to limit viral dissemination, while cellular immunity plays a vital role in controlling the replication and clearance of the virus. A central aspect of herpesvirus biology is their ability to establish latency in the host organism and reactivate in response to various stress factors, which has a significant impact on their epidemiology and the dynamics of infectious foci. This review provides a detailed synthesis of the taxonomy, general structure, replication cycle, transmission and excretion mechanisms, immune responses, and latency and reactivation processes of EHV types 1 and 4 (EHV-1 and EHV-4), the two major agents responsible for respiratory, reproductive, and neurological diseases in equines.

EHV: Equine Herpes Virus; EMPF: Equine Multinodular Pulmonary Fibrosis; DNA: Deoxyribonucleic Acids; RNA: Ribonucleic Acids; UL: Unique Long region; US: Unique Short region; TR: Terminal Repeat region; IR: Internal Repeat region; ORFs: Open Reading Frames; MHC-I: Major Histocompatibility Complex class I; CHO-K1 cell: Chinese Hamster Ovary subclone K1 cell; ED: Equine Dermal cells; RK13: Rabbit Kidney cells; RNAP-II: RNA polymerase II; ETIF: EHV Transinducing Factor; CTLs: Cytotoxic T Lymphocytes; IgM: Immunoglobulin M; IgG: Immunoglobulin G; IgA: Immunoglobulin A; vCKBP: viral Chemokine Binding Protein

Introduction

Horses are natural hosts for several herpesviruses belonging to the Alphaherpesvirinae and Gammaherpesvirinae subfamilies. Equine herpesvirus types 1, 3, and 4 (EHV-1, EHV-3, and EHV-4) are particularly well recognised among the alphaherpesviruses, whereas EHV-2 and EHV-5 are also widely distributed among equine populations [1]. Donkeys harbour their own set of herpesviruses — AHV-1, AHV-2, and AHV-3 — which share certain biological characteristics with their equine counterparts, but which are adapted to their specific host [1]. Before advances in virological and molecular techniques clarified their distinct identities, EHV-1 and EHV-4 were historically thought to represent either a single viral entity or closely related subtypes of the same virus [2]. This long-standing confusion was largely due to their considerable antigenic and genetic cross-reactivity, which continues to complicate diagnostic differentiation [1,2].

From a clinical and economic standpoint, EHV-1 and EHV-4 are the herpesviruses that pose the greatest threat to the equine industry worldwide [1]. EHV-1, in particular, is highly prevalent and capable of causing a broad spectrum of disease, ranging from subclinical infections to severe pathological outcomes with substantial welfare and economic consequences [3]. Both EHV-1 and EHV-4 are commonly associated with febrile rhinopneumonia, particularly in young horses. However, EHV-1 has additional pathogenic potential; it can lead to abortion storms, neonatal death, or equine herpesvirus myeloencephalopathy (EHM) [1,3]. EHM is a neurological syndrome driven by necrotising vasculitis and thrombosis, resulting from lytic replication of the virus in the endothelial cells that line blood vessels. This vascular tropism is a hallmark of EHV-1 virulence and central to the development of its most severe clinical manifestations [1].

EHVs, such as EHV-2 and EHV-5, are widespread but exhibit a different pathogenic profile. Their infections are often associated with non-specific and variable clinical presentations, ranging from mild respiratory disease in individual horses to outbreaks involving groups of young animals [4]. In contrast, EHV-3 causes a distinct, generally self-limiting venereal disease that affects the external genitalia. This disease is commonly referred to as equine coital exanthema and is of particular concern in breeding operations [1].

Due to the significant health, welfare, and economic impact of alphaherpesvirus infections, particularly those caused by EHV-1 and EHV-4, there is an ongoing need to improve our understanding of their biology. This review, therefore, focuses primarily on these two viruses, highlighting their taxonomy, structural organisation, replication mechanisms, modes of transmission and excretion, interactions with the equine immune system, and the dynamics of latency and reactivation.

Herpesvirus in equines

To date, ten herpesviruses have been identified in equids, with five belonging to the Alphaherpesvirinae subfamily and five to the Gammaherpesvirinae subfamily (Table 1). Horses are the natural hosts of alphaherpesvirus types 1 (EHV-1), 3 (EHV-3), and 4 (EHV-4), and gammaherpesvirus types 2 (EHV-2) and 5 (EHV-5). Donkeys serve as hosts for asinine herpesvirus types 1 (AHV-1) and 3 (AHV-3), which are homologues of EHV-1 and EHV-3, respectively, as well as asinine gammaherpesvirus type 2 (AHV-2) [1,5-8]. In 2002, two additional herpesviruses (AHV-4 and AHV-5) were isolated from the lungs of donkeys presenting with interstitial pneumonia [9].

The discovery of a novel neurotropic virus related to EHV-1, which was isolated from a gazelle and is known as Gazelle herpesvirus-1 or EHV-9, suggests that the diversity of equine herpesviruses may be greater than is currently recognised [1,8,10]. Furthermore, an unidentified herpesvirus was isolated in 2008 from a donkey exhibiting neurological symptoms [11].

Five equine herpesviruses (EHVs) have been isolated from horses. The alphaherpesviruses EHV-1 and EHV-4, in particular, are primary respiratory pathogens that have been associated with outbreaks of respiratory disease. In addition, EHV-1 is responsible for outbreaks of abortion and, less frequently, neurological disorders [12]. EHV-1 and EHV-4 are considered the most clinically, economically, and epidemiologically significant equine herpesviruses [1].

The gammaherpesviruses EHV-2 and EHV-5 are closely related and have been detected in equine populations worldwide [12]. EHV-2 has been identified in clinically healthy horses, as well as in horses affected by keratoconjunctivitis [13]. It has also been associated with upper respiratory tract disease, conjunctivitis, lymphadenopathy, and coughing [14]. Several studies have suggested a link between equine multinodular pulmonary fibrosis (EMPF) and EHV-5 infection. While the exact role of EHV-5 in EMPF pathogenesis remains unclear, it is considered a potential aetiological agent or an important cofactor in the development of this condition [15-17].

Taxonomy

These herpesviruses are classified within the order Herpesvirales, which comprises three families. The Herpesviridae family includes viruses that infect mammals, birds, and reptiles, while the Alloherpesviridae family encompasses those that infect fish and amphibians. Currently, the Malacoherpesviridae family contains only one known member: the ostreid herpesvirus [18,19].

Within the Herpesviridae family, viruses are divided into three subfamilies: Alphaherpesvirinae, Betaherpesvirinae, and Gammaherpesvirinae. The Alphaherpesvirinae subfamily is considered the most evolutionarily divergent, exhibiting a broad host range that includes humans, with representatives such as Herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 (HHV-1 and HHV-2), as well as Varicella-zoster virus (HHV-3). This subfamily also encompasses various animal species, including Bovine herpesvirus-1 (BoHV-1) and Feline herpesvirus-1 (FeHV-1) [18,20].

Six equine herpesviruses are classified within this subfamily, all belonging to the Varicellovirus genus [8,18,21]. EHV-6 and EHV-8 naturally infect donkeys, while EHV-9 has been isolated from gazelles [1,8,10]. The remaining three — EHV-1, EHV-3, and EHV-4 — have horses as their natural hosts, with EHV-1 and EHV-4 being the focus of the present review (Table 2).

General structure

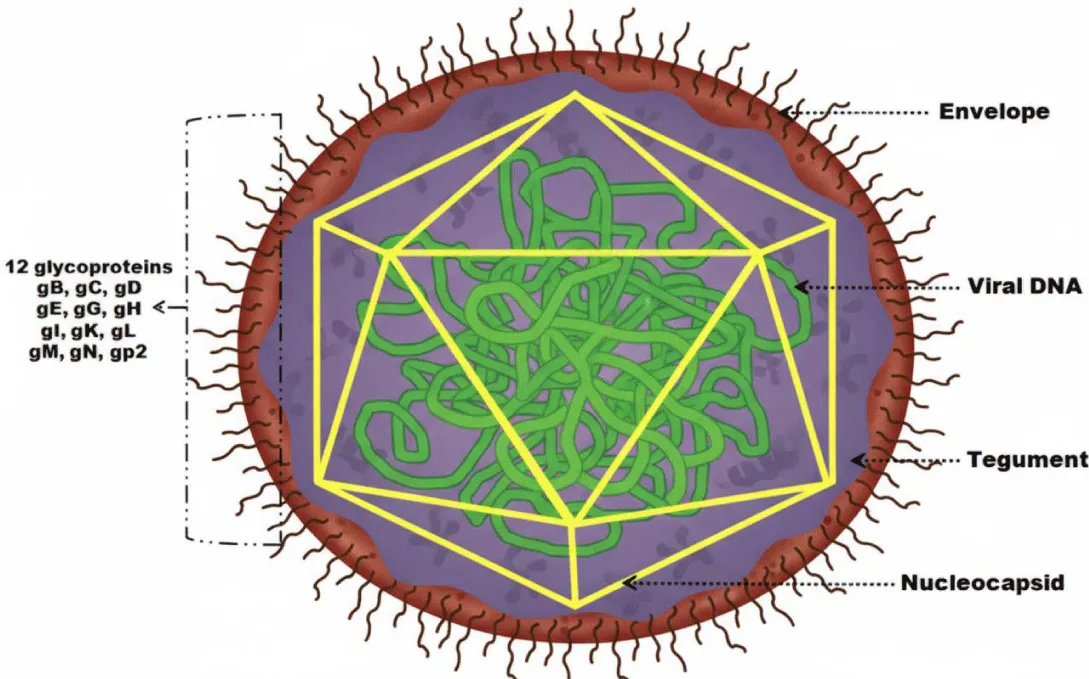

A typical herpesvirion consists of a core containing linear, double-stranded DNA, which is enclosed within an icosahedral capsid. This is surrounded by a proteinaceous tegument layer and an outer lipid envelope studded with viral glycoprotein spikes [22,23]. Due to variations in envelope size, herpesvirions range in diameter from approximately 120 to 250 nm [23]. Figure 1 shows the general structure of EHV.

Viral genome

Both EHV-1 and EHV-4 have a linear, double-stranded DNA genome with an identical overall organisation. This consists of a unique long (UL) region joined to a unique short (US) region. The US region is flanked by two inverted repeat sequences, known as the terminal repeat (TR) and internal repeat (IR) regions [24,25].

Consequently, genes located within these repeated segments are duplicated in the genome. Despite their similar genome sizes and extensive collinearity, EHV-1 and EHV-4 remain genetically and phenotypically distinct viruses. The EHV-1 genome is approximately 150 kilobases (kb) in length and encodes 76 open reading frames (ORFs), four of which are duplicated in the repeat regions, yielding a total of 80 ORFs. Of these, 63 are located in the UL region, nine in the US region, and four within the IR regions. The EHV-4 genome is slightly smaller at 145 kb and encodes 76 ORFs, with three duplicated in the repeat regions, giving a total of 79 ORFs. Each of the 76 EHV-4 genes has a homologous counterpart in EHV-1, arranged in the same order. The 63 ORFs within the UL region exhibit a conserved collinear arrangement similar to that observed in Herpes simplex virus (HSV) and Varicella-zoster virus (VZV). However, the arrangement of several genes located in the IR and US regions differs from that of other alphaherpesviruses. The EHV-2 genome, among other equine herpesviruses, is larger (184 kb) and contains 79 ORFs, 77 of which are predicted to encode proteins [24-26]. Similarly, the EHV-3 genome encodes 76 ORFs, including four duplicated within the repeat regions [27].

Both EHV-1 and EHV-4 harbour five unique genes (designated 1, 2, 67, 71, and 75) that have no known homologues in other sequenced herpesviruses. These genes have been the focus of considerable research due to their potential roles in viral pathogenesis. Although their precise functions remain unclear, in vitro and murine model studies have not yet identified any distinct contributions of these genes to virulence [25].

The reported genome sizes of the main equine herpesviruses are as follows: EHV-2: 184 kbp; EHV-3: 144 kbp; EHV-5: 179 kbp. The genome size of EHV-9 has yet to be determined, but is presumed to be similar to that of EHV-1. The genomes of EHV-1, EHV-3, and EHV-4 exist in two isomeric forms because the short (S) region can invert relative to the fixed orientation of the unique long (UL) region. The S region consists of a central segment of unique sequences (US) flanked by a pair of inverted repeat sequences (IRs). In contrast, the genomes of EHV-2 and EHV-5 exist as a single isomeric form comprising a large central segment of unique sequences (approximately 149 kbp) flanked by direct terminal repeats. Each terminal repeat measures approximately 18 kbp, resulting in a total genome size ranging from 179 to 184 kbp [26].

Varying degrees of DNA homology have been reported among EHV-1, EHV-2, EHV-3, EHV-4, EHV-5, and EHV-9. The genomic sequences of EHV-1, EHV-3, EHV-4, and EHV-9 exhibit conserved collinearity, with homologous regions distributed throughout their genomes. EHV-1 and EHV-4 share 55% - 84% nucleotide sequence identity, are antigenically closely related, and exhibit cross-neutralising antibodies. The level of identity between EHV-1 and EHV-9 is even higher than that between EHV-1 and EHV-4. In contrast, EHV-1 and EHV-2 show negligible sequence similarity, as do EHV-2 and EHV-3. The nucleotide identity between EHV-1 and EHV-3 is approximately 10% [26].

Among the equine alphaherpesviruses, EHV-3 is the most divergent, showing an overall nucleotide sequence homology of only 62.1–64.9% compared to other equine herpesviruses [27]. Finally, EHV-2 and EHV-5 are distinct but closely related gammaherpesviruses, sharing approximately 60% sequence homology at both the nucleotide and amino acid levels [4,26].

Capsid

The capsid of all herpesviruses exhibits an icosahedral structure with an outer diameter ranging from 125 to 130 nm. This structure is composed of 162 capsomeres, including 12 pentons and 150 hexons. Each penton contains five copies of the major capsid protein, while each hexon contains six copies [22,28].

Integument

The tegument of the herpesvirus is a self-supporting layer made up of thousands of tightly organised protein molecules that occupy the space between the capsid and the viral envelope [22,29].

Envelope

The nucleocapsid and tegument of herpesviruses are enclosed within a lipid envelope displaying eleven viral glycoproteins on its surface (Table 3). The eleven glycoproteins of EHV-1 — gB (gp14), gC (gp13), gD (gp18), gE, gG, gH, gI, gK, gL, gM, and gN — are conserved across alphaherpesviruses and are named according to the nomenclature established for HSV-1 [22]. Unlike HSV-1 and most other alphaherpesviruses, EHV-1 encodes an additional glycoprotein, gp2, which is only found in EHV-4 and AHV-3 [22]. In purified EHV-1 virions, gB, gC, gD, gG, gH, gL, gM, and gp2, as well as the tegument protein VP13/14, are associated with the particle [26].

Glycoproteins play essential roles throughout the viral infection cycle, including attachment, penetration, release, and cell-to-cell spread [22,26,30]. In EHV-1, these functions have specifically been confirmed for gB, gD, gM, and gp2; the latter two are non-essential for viral growth. Conversely, EHV-1 mutants lacking gB or gD cannot replicate in cell culture due to defects in viral entry and propagation from infected to uninfected cells [26]. Glycoproteins gD and gG also appear to play a critical role in the infection and manipulation of equine mononuclear cells [30]. Functional analyses of the remaining glycoproteins have not yet been fully conducted, although the development of combined mutant viruses using infectious DNA clones now enables such studies [26].

Replication cycle

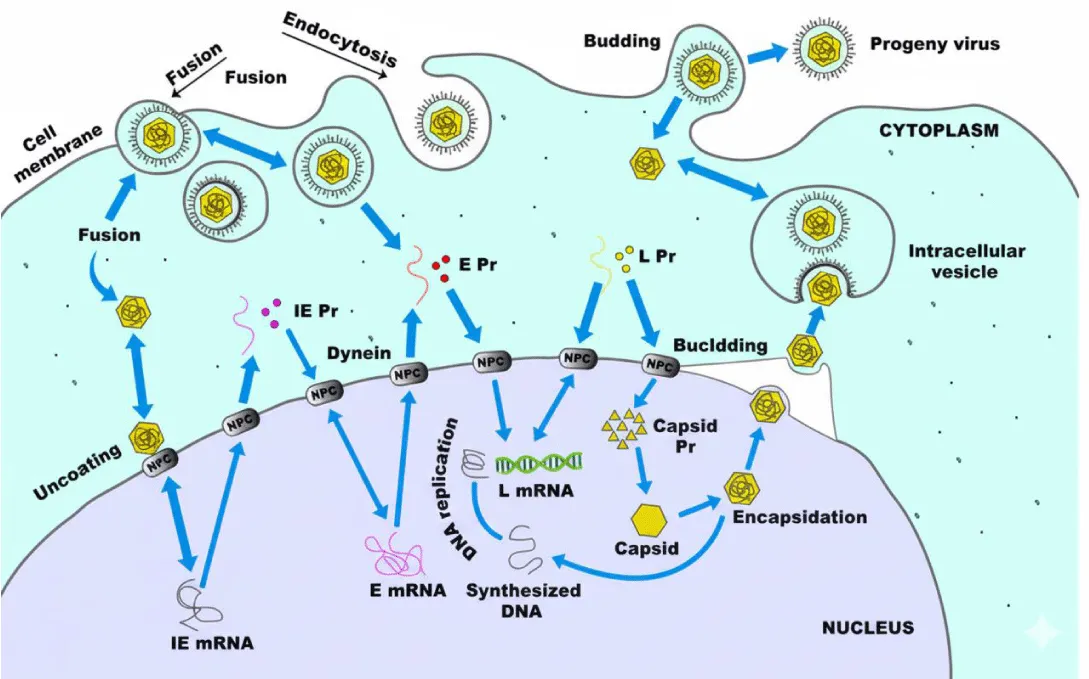

The complete replication cycle of EHV-1 or EHV-4 takes around 20 hours [25]. During this time, a highly organised series of events takes place: attachment to the host cell membrane, membrane fusion and penetration, translocation of viral DNA to the nucleus, replication of viral DNA, synthesis of viral proteins, assembly of the capsid, egress from the nucleus, envelopment and release of the virion, and ultimately, lysis of the host cell [25]. Figure 2 shows the EHV replication cycle.

Virus attachment

Herpesvirus entry into target cells is mediated by interactions with multiple cellular receptors that facilitate attachment, trigger signalling cascades, or induce viral internalisation [31]. Infection begins when the virion binds to the cell membrane through the interaction between gC and gB and the heparan sulfate moieties of cell surface proteoglycans [32,33].

Virus entry

Following attachment, entry into the cell can occur either through direct fusion of the viral envelope with the plasma membrane or via endocytosis, followed by fusion with the endosomal membrane [34]. Glycoprotein gD is essential for inducing envelope fusion with the host cell membrane, and molecules of the equine major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC-I) act as entry receptors by binding to EHV-1 gD [35,36].

The mechanism of entry varies with cell type: EHV-1 enters CHO-K1 cells via endocytosis or phagocytosis, but enters equine dermal (ED) or rabbit kidney (RK13) cells through direct membrane fusion [37]. Entry into CHO-K1 cells does not require clathrin or caveolae [37]. Following fusion, the capsid is released into the cytoplasm and transported to the nucleus for viral replication [34]. Efficient transport to the nucleus depends on the integrity of the microtubule network and the motor protein dynein; the cellular kinase ROCK1 also contributes to this process [34]. EHV-1 infection also requires the activation of host cell signalling pathways [37]. Upon nuclear entry, the viral DNA-protein complex is released, rapidly shutting down host macromolecular synthesis in favour of viral replication [23].

Genome replication

During infection, the expression of viral genes in EHV-1 and EHV-4 is temporally regulated in three sequential phases: immediate early (IE), early (E), and late (L) [25,38]. This tightly controlled transcriptional programme is the result of complex interactions between viral and cellular factors at transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels, including structural differences in promoter architecture for each gene class [38]. Consequently, three classes of viral mRNA—α, β, and γ—are transcribed sequentially by cellular RNA polymerase II (RNAP II) [23].

Immediate early (α) RNAs are processed into small RNAs (smRNAs) and translated into α proteins, which initiate the transcription of early (β) smRNAs. Translation of β smRNAs produces early (β) proteins, some of which suppress further α RNA transcription [23]. As RNAP-II mediates herpesvirus transcription, most viral promoters share DNA motifs with host genes; however, promoter complexity generally decreases from immediate early to late genes [38].

Several IE polypeptides are expressed, with the primary protein, IE1 (203kDa), localised in the nucleus. IE1 is a phosphoprotein that can transactivate other viral genes and self-regulate its own transcription [26]. Following IE protein synthesis, approximately 45 early transcripts become detectable [26]. Among these, four early proteins act as regulatory factors: IR4 (EICP22), UL5 (EICP27), EICP0 (UL63), and IR2 [26]. Additionally, the unique IR3 gene of EHV-1 encodes a small transcript with regulatory function [26].

Viral DNA replication then commences, utilising select α and β proteins alongside host factors [23]. This is followed by late (γ) gene transcription, which produces γ small RNAs (smRNAs) that are translated into γ proteins. While approximately 29 late transcripts have been detected, only a subset of their protein products has been identified and characterised [26]. Viral DNA replication begins around four hours post-infection and requires viral DNA polymerase [26]. The initiation of DNA synthesis also triggers late gene expression and the production of the late regulatory protein EHV transinducing factor (ETIF, 60kDa), which performs at least three critical functions during EHV-1 replication [26].

Over 70 viral proteins are expressed throughout the replication cycle. Most α and β proteins function as enzymes or DNA-associated factors, whereas γ proteins predominantly serve structural roles [23]. Expression is subject to complex regulation at transcriptional and translational levels to ensure the precise timing and coordination of viral replication [23].

Virus assembly

Viral DNA replication occurs in the nucleus, where newly synthesised DNA is packaged into pre-formed immature capsids [23]. As observed in other herpesviruses, EHV-1 maturation involves interactions between mature nucleocapsids and the inner nuclear membrane. This results in the formation of enveloped particles [26]. This process involves the completion of DNA encapsidation within the nucleocapsids and their association with modified regions of the nuclear envelope. Capsids become visible approximately six hours post-infection [26].

The nucleocapsids localise to the inner layer of the nuclear membrane within the perinuclear space, acquiring a primary envelope [39]. This primary envelope subsequently fuses with the outer nuclear membrane, releasing naked nucleocapsids into the cytoplasm. Complete envelopment occurs as the capsids bud through the cytoplasmic membrane. In the cytoplasm, naked nucleocapsids acquire their tegument and, subsequently, tegumented capsids obtain their final envelope by budding into vesicles of the trans-Golgi network [39-42].

Virus release

Mature virions accumulate within cytoplasmic vacuoles and are released by either exocytosis or cell lysis [23]. The envelope of infectious EHV-1 virions is predominantly composed of glycoproteins [26]. Viral proteins are also incorporated into the plasma membrane, where they participate in cell fusion and function as Fc receptors. They also serve as targets for immune-mediated cytolysis [23]. Intranuclear inclusion bodies are a hallmark of herpesvirus infection in both animals and cell cultures. Recent studies indicate that the EHV-1 trans-inducing factor (ETIF) is essential for virion maturation and release [26].

Virus transmission and shedding

EHV-1 and EHV-4 infections can be transmitted through direct contact between horses and indirectly via contaminated animals, humans, or objects [25,43,44]. The most common route of transmission is respiratory, via the inhalation of aerosolised droplets containing viral particles from respiratory secretions [3,25,26,43]. Infection can also occur through the ingestion of material contaminated with nasal discharge [3,25,44]. Major sources of the virus include respiratory secretions from horses and foals, as well as foetal and placental tissues and fluids from aborted foetuses [3,25,45].

Horses and foals are most contagious during the acute phase of infection and may also shed the virus when it reactivates from latency, which is thought to persist lifelong [25,44]. Foals infected with EHV-4 exhibit prolonged and abundant nasal shedding, whereas most horses cease viral excretion within one to two weeks post-infection [46]. Reactivation of latent EHV-1 results in brief nasal shedding, typically lasting around two days [47]. EHV-1 can also be excreted in the semen of infected stallions, and transmission via semen, through either natural mating or artificial insemination, has been suggested based on evidence from other herpes viruses in different species [48-50].

The virus can persist in the environment for extended periods, with survival ranging from 14 to 45 days outside the host [44]. EHV-1 remains infectious for up to one week at room temperature on surfaces such as paper, wood, or rope, and for up to 35 days on horsehair or burlap [51].

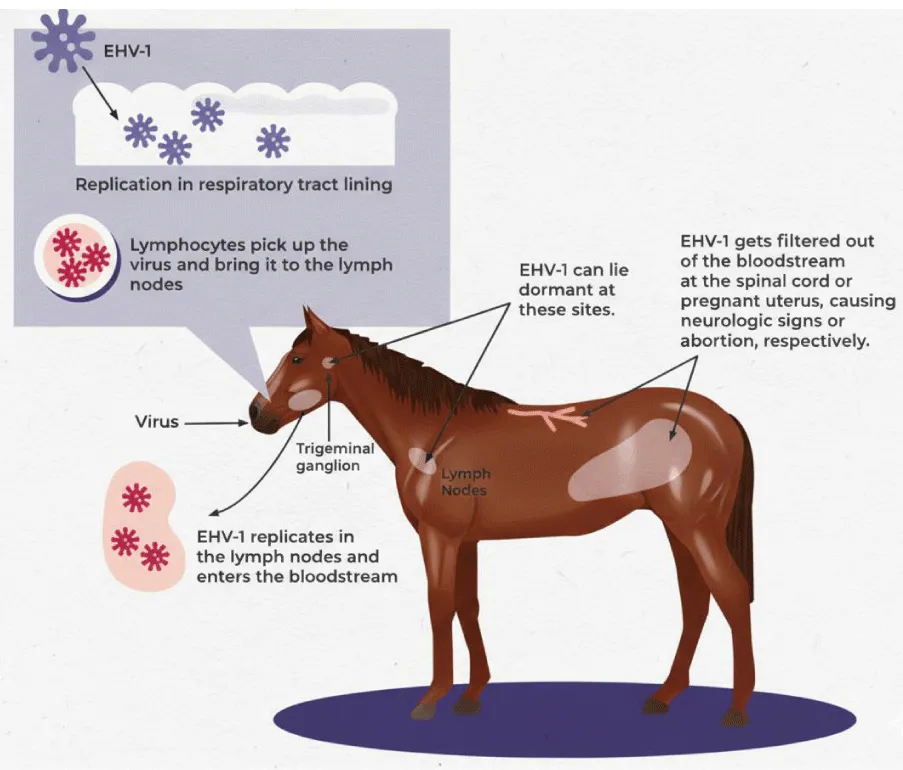

Pathogenesis

Immunity

EHV infection stimulates a multifaceted, tissue-dependent immune response that involves mucosal surfaces and deeper lymphoid structures. These responses include finely tuned cellular mechanisms, in which CD8⁺ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) play a pivotal role in recognising and eliminating infected cells [25]. Protective immunity against EHV relies on the coordinated interaction between local mucosal defences and systemic humoral and cellular responses. As EHV infections are predominantly cell-associated and can spread directly between adjacent cells without the release of extracellular virions being required, cell-mediated immunity is particularly important for controlling viral dissemination [21]. It is also the main determinant of long-lasting protection; humoral immunity alone, despite its role in viral neutralisation, cannot prevent infection or recurrence of the disease [25,26].

Immunity following natural respiratory tract infection tends to be short-lived, even though neutralising antibodies remain detectable in the blood for prolonged periods [44]. Nevertheless, this post-infection immunity provides substantial protection against reinfection for approximately three to six months [25]. With repeated viral exposure, horses may gradually develop stronger and more comprehensive immune defences, leading not only to clinical protection, but also, in some cases, to sterile immunity, meaning that subsequent exposures do not result in virus shedding or detectable viremia. However, due to the transient nature of these immune responses, horses are susceptible to multiple EHV infections throughout their lifetime, although subsequent episodes typically present with milder clinical signs than the primary infection [44].

Infection with EHV-1 and EHV-4 induces characteristic and dynamic changes in circulating leukocyte populations. During the early stages of infection, typically between days 7 and 13 after exposure, horses experience marked leukopenia, including lymphopenia and neutropenia, as well as a significant decrease in CD8⁺ T cells. This immunosuppressed phase is followed by a rebound leukocytosis, primarily driven by lymphocyte expansion, which generally persists from days 21 to 28 [25]. EHV-1, in particular, has been shown to transiently suppress components of the immune system, most notably peripheral blood monocytes, potentially through cytokine-mediated inhibition or dysregulation. As the infection progresses, the adaptive immune system mounts a robust response, leading to the proliferation of virus-specific CTLs that can recognise and eliminate infected cells [21]. Although fewer studies have focused specifically on EHV-4, available evidence suggests that cytotoxic T cell responses are equally crucial for controlling this virus due to its predominantly cell-associated nature [44].

Alongside these cellular responses, EHV infection induces potent systemic humoral immunity. This begins with an early surge in immunoglobulin M (IgM), which rises rapidly but declines within three months. This is followed by the development of immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies, which increase more gradually but persist for significantly longer, often for over a year [25]. In contrast, circulating immunoglobulin A (IgA) levels remain relatively low in convalescent serum samples [25]. Neutralising antibodies typically appear around one week after primary infection, reaching peak levels several weeks later. Repeated exposure to EHV-1 or EHV-4 enhances the development of cross-reactive neutralising antibodies, which provide broader protection against related viral strains [26].

However, mucosal immunity represents the first line of defence against EHV invasion. At the respiratory epithelium, which is the initial site of viral entry, local IgA production plays a crucial role in neutralising viral particles and preventing them from infecting epithelial cells [21]. Although IgA responses are relatively short-lived following a single infection, they become more persistent with repeated exposure, highlighting the importance of natural boosting in endemic environments. In young horses, protection is also influenced by maternal immunity: foals born to mares with circulating EHV antibodies receive passive immunity by ingesting high-quality colostrum. This protection, which is dominated by IgG, can last up to 180 days provided that the quantity and timing of colostrum intake are adequate [44].

Latency and reactivation

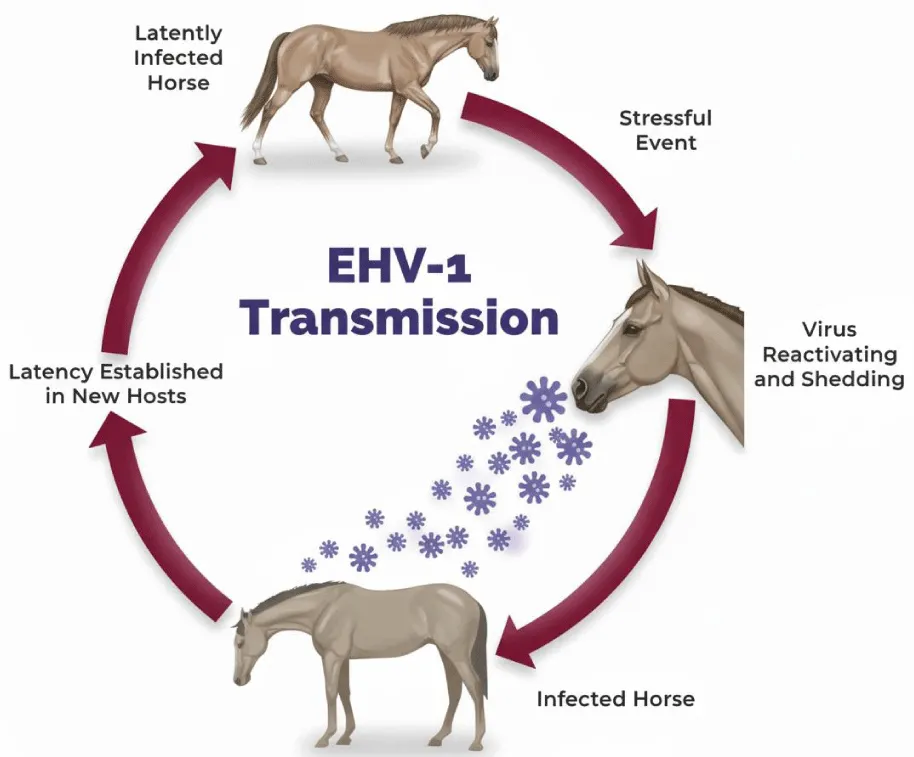

Latency and reactivation are central features of EHV-1 and EHV-4 infections, playing a critical role in their prevalence among horses [25]. Consequently, experimental studies investigating the mechanisms of latency and reactivation in horses have often produced inconclusive or limited results [2].

The initial respiratory infection that establishes latency can occur months or even years before EHV-1-associated abortion or neurological disease becomes apparent [52]. The vast majority of recovered horses harbour latent EHV infections for extended periods, often for life [25]. Both EHV-1 and EHV-4 establish latency in the lymphoreticular system and in circulating CD8⁺ T cells and neuronal ganglia, including the trigeminal ganglia [2,25]. Although viral DNA can be detected in other tissues, it remains unclear whether these sites support reactivation. Attempts to recover EHV-1 from the cranial ganglia of experimentally or naturally infected horses using co-culture methods have frequently been unsuccessful [2].

Latently infected cells serve as a reservoir for periodic viral reactivation, leading to the shedding of infectious virus and sustaining transmission within the horse population [25]. Consequently, sporadic cases of abortion and neurological disease can occur in closed herds without an external source of EHV-1 infection [53].

Latent EHV-1 and EHV-4 can undergo reactivation (recrudescence) under certain conditions. Periodically, latently infected horses experience episodes of reactivation, during which infectious viruses are shed in respiratory secretions and can potentially transmit the infection to susceptible horses [25]. Field observations suggest that reactivation frequently follows stressful events such as transportation, handling, relocation, weaning, sales, competitions, or disturbances to social hierarchies [25]. In experimental settings, EHV-1 can be reactivated by administering high doses of glucocorticoids, and recrudescence may be accompanied by clinical signs [54]. Reactivating EHV-4 in experimental settings has proven more challenging, as it may not fully replicate natural reactivation [2]. This difficulty contrasts with certain other animal alphaherpesviruses, such as bovine and feline herpesviruses, which can be readily reactivated with corticosteroids [2].

Clinical consequences, such as abortion or neurological disease, may result from local viral reactivation. For example, EHV-1 reactivation within the blood vessels of the uterus, placenta, or central nervous system can lead to endothelial infection and thrombo-ischemic lesions [25]. Regardless of the anatomical site of reactivation, latency and recrudescence are critical factors in the epidemiology of EHV-1-associated abortion and neurological disease [25]. Figures 3,4 show the role of latency and reactivation in the persistence and transmission of equine herpesviruses. Table 4 shows he equine herpesviruses and their main clinical associations.

Conclusion

EHV-1 and EHV-4 are important subjects of study due to their significant economic and epidemiological impact in veterinary medicine. Understanding the taxonomy and structural characteristics of equine herpesviruses is key to grasping their biology and pathogenic mechanisms. Molecular analyses, including studies of DNA sequences and specific genomic regions, have revealed distinct differences between these viruses. The functions of various envelope glycoproteins have been identified and characterised, thereby enhancing our understanding of viral entry and spread. Extensive research into viral replication, transmission, and excretion has provided valuable insights into the epidemiology of equine herpesviruses. Furthermore, substantial progress has been made in elucidating host immune responses, as well as the mechanisms underlying viral latency and reactivation.

- Patel JR, Heldens J. Equine herpesviruses 1 (EHV-1) and 4 (EHV-4) – epidemiology, disease and immunoprophylaxis: A brief review. Vet J. 2005;170:14-23. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tvjl.2004.04.018

- Crabb BS, Studdert MJ. Equine herpesvirus 4 (equine rhinopneumonitis virus) and 1 (equine abortion virus). Adv Virus Res. 1995;45:153-190. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/s0065-3527(08)60060-3

- Lunn DP, Davis-Poynter N, Flaminio MJBF, Horohov DW, Osterrieder K, Pusterla N. Equine Herpesvirus-1 Consensus Statement. J Vet Intern Med. 2009;23:450-461. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-1676.2009.0304.x

- Fortier G, van Erck E, Pronost S, Lekeux P, Thiry E. Equine gammaherpesviruses: Pathogenesis, epidemiology and diagnosis. Vet J. 2010;186:148-156. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tvjl.2009.08.017

- Browning GF, Ficorilli N, Studdert MJ. Asinine herpesvirus genomes: comparison with those of the equine herpesviruses. Arch Virol. 1988;101:183-190. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01310999

- Crabb BS, Studdert MJ. Comparative studies of the proteins of equine herpesviruses 4 and 1 and asinine herpesvirus 3: antibody response of the natural hosts. J Gen Virol. 1990;71:2033-2041. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1099/0022-1317-71-9-2033

- Ficorilli N, Studdert MJ, Crabb BS. The nucleotide sequence of asinine herpesvirus 3 glycoprotein G indicates that the donkey virus is closely related to equine herpesvirus 1. Arch Virol. 1995;140:1653-1662. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01322539

- Ma G, Azab W, Osterrieder N. Equine herpesviruses type 1 (EHV-1) and 4 (EHV-4) – Masters of co-evolution and a constant threat to equids and beyond. Vet Microbiol. 2013;167:123-134. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetmic.2013.06.018

- Kleiboeker SB, Schommer SK, Johnson PJ, Ehlers B, Turnquist SE, Boucher M. Association of two newly recognized herpesviruses with interstitial pneumonia in donkeys (Equus asinus). J Vet Diagn Invest. 2002;14:273-280. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1177/104063870201400401

- Fukushi H, Tomita T, Taniguchi A, Ochiai Y, Kirisawa R, Matsumura T, et al. Gazelle herpesvirus 1: a new neurotropic herpesvirus immunologically related to equine herpesvirus 1. Virology. 1997;227:34-44. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1006/viro.1996.8296

- Vengust M, Wen X, Bienzle D. Herpesvirus-associated neurological disease in a donkey. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2008;20:820-823. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1177/104063870802000620

- Gilkerson JR, Bailey KE, Diaz-Méndez A, Hartley CA. Update on viral diseases of the equine respiratory tract. Vet Clin North Am Equine Pract. 2015;31:91-104. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cveq.2014.11.007

- Kershaw O, von Oppen T, Glitz F, Deegen E, Ludwig H, Borchers K. Detection of equine herpesvirus type 2 (EHV-2) in horses with keratoconjunctivitis. Virus Res. 2001;80:93-99. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/s0168-1702(01)00299-4

- Borchers K, Wolfinger U, Ludwig H, Thein P, Baxi S, Field HJ, et al. Virological and molecular biological investigations into equine herpesvirus type 2 (EHV-2) experimental infections. Virus Res. 1998;55:101-106. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/s0168-1702(98)00028-8

- Williams KJ, Maes R, Del Piero F, Lim A, Wise A, Bolin DC, et al. Equine multinodular pulmonary fibrosis: a newly recognized herpesvirus-associated fibrotic lung disease. Vet Pathol. 2007;44:849-862. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1354/vp.44-6-849

- Wong DM, Belgrave RL, Williams KJ, Del Piero F, Alcott CJ, Bolin SR, et al. Multinodular pulmonary fibrosis in five horses. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2008;232:898-905. Available from: https://doi.org/10.2460/javma.232.6.898

- Verryken K, Saey V, Maes S, Borchers K, Van de Walle G, Ducatelle R, et al. First report of multinodular pulmonary fibrosis associated with equine herpesvirus 5 in Belgium. Vlaams Diergeneeskd Tijdschr. 2010;79:297-301. Available from: https://doi.org/10.21825/vdt.87459

- Davison AJ, Eberle R, Ehlers B, Hayward GS, McGeoch DJ, Minson AC, et al. The order Herpesvirales. Arch Virol. 2009;154:171-177. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00705-008-0278-4

- Mineur F, Provan J, Arnott G. Phylogeographical analyses of shellfish viruses: inferring a geographical origin for ostreid herpesviruses OsHV-1 (Malacoherpesviridae). Mar Biol. 2015;162:181-192. Available from: https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/doi/full/10.5555/20153032712

- Mori I, Nishiyama Y. Herpes simplex virus and varicella-zoster virus: why do these human alphaherpesviruses behave so differently from one another? Rev Med Virol. 2005;15:393-406. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/rmv.478

- Reed SM, Toribio RE. Equine herpesvirus 1 and 4. Vet Clin Equine. 2004;20:631-642. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cveq.2004.09.001

- Paillot R, Case R, Ross J, Newton R, Nugent J. Equine herpes virus-1: virus, immunity and vaccines. Open Vet Sci J. 2008;2:68-91. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.2174/1874318808002010068

- Mettenleiter TC. Herpesvirus assembly and egress. J Virol. 2002;76:1537-1547. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1128/jvi.76.4.1537-1547.2002

- MacLachlan NJ, Dubovi EJ. Herpesvirales. In: Fenner’s Veterinary Virology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2011. p. 179-201.

- Telford EAR, Watson MS, Perry J, Cullinane AA, Davison AJ. The DNA sequence of equine herpesvirus-4. J Gen Virol. 1998;79:1197-1203. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1099/0022-1317-79-5-1197

- Slater J. Equine herpesviruses. In: Sellon DC, Long MT, editors. Equine Infectious Diseases. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2014. p. 151-168.

- O’Callaghan DJ, Osterrieder N. Herpesviruses of horses. In: Mahy B, van Regenmortel M, editors. Desk Encyclopedia of Animal and Bacterial Virology. 1st ed. Elsevier; 2008. p. 140-148.

- Sijmons S, Vissani A, Tordoya MS, Muylkens B, Thiry E, Maes P, et al. Complete genome sequence of equid herpesvirus 3. Genome Announc. 2014;2. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1128/genomea.00797-14

- Brown JC, Newcomb WW. Herpesvirus capsid assembly: insights from structural analysis. Curr Opin Virol. 2011;1:142-149. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coviro.2011.06.003

- Owen D, Crump C, Graham S. Tegument assembly and secondary envelopment of alphaherpesviruses. Viruses. 2015;7:5084-5114. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3390/v7092861

- Osterrieder N, Van de Walle GR. Pathogenic potential of equine alphaherpesviruses: the importance of the mononuclear cell compartment in disease outcome. Vet Microbiol. 2010;143:21-28. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetmic.2010.02.010

- Heldwein EE. gH/gL supercomplexes at early stages of herpesvirus entry. Curr Opin Virol. 2016;18:1-8. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coviro.2016.01.010

- Shieh MT, WuDunn D, Montgomery RI, Esko JD, Spear PG. Cell surface receptors for herpes simplex virus are heparan sulfate proteoglycans. J Cell Biol. 1992;116:1273-1281. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1083/jcb.116.5.1273

- Osterrieder N. Construction and characterization of an equine herpesvirus 1 glycoprotein C negative mutant. Virus Res. 1999;59:165-177. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/s0168-1702(98)00134-8

- Frampton AR, Uchida H, von Einem J, Goins WF, Grandi P, Cohen JB, et al. Equine herpesvirus type 1 (EHV-1) utilizes microtubules, dynein, and ROCK1 to productively infect cells. Vet Microbiol. 2010;141:12-21. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetmic.2009.07.035

- Spear PG, Longnecker R. Herpesvirus entry: an update. J Virol. 2003;77:10179-10185. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1128/jvi.77.19.10179-10185.2003

- Sasaki M, Hasebe R, Makino Y, Suzuki T, Fukushi H, Okamoto M, et al. Equine major histocompatibility complex class I molecules act as entry receptors that bind to equine herpesvirus-1 glycoprotein D. Genes Cells. 2011;16:343-357. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2443.2011.01491.x

- Frampton AR, Stolz DB, Uchida H, Goins WF, Cohen JB, Glorioso JC. Equine herpesvirus 1 enters cells by two different pathways, and infection requires activation of the cellular kinase ROCK1. J Virol. 2007;81:10879-10889. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1128/jvi.00504-07

- Gruffat H, Marchione R, Manet E. Herpesvirus late gene expression: a viral-specific pre-initiation complex is key. Front Microbiol. 2016;7. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2016.00869

- Mettenleiter TC. Budding events in herpesvirus morphogenesis. Virus Res. 2004;106:167-180. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virusres.2004.08.013

- Granzow H, Klupp BG, Fuchs W, Veits J, Osterrieder N, Mettenleiter TC. Egress of alphaherpesviruses: comparative ultrastructural study. J Virol. 2001;75:3675-3684. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1128/jvi.75.8.3675-3684.2001

- Mettenleiter TC, Klupp BG, Granzow H. Herpesvirus assembly: a tale of two membranes. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2006;9:423-429. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mib.2006.06.013

- Hussey GS, Landolt GA. Equine alphaherpesviruses. In: Sprayberry KA, Robinson NE, editors. Robinson’s Current Therapy in Equine Medicine. 7th ed. Elsevier; 2015. p. 158-161. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/chapter/edited-volume/abs/pii/B9781455745555000376

- Constable PD, Hinchcliff KW, Done SH, Grünberg W. Equine viral rhinopneumonitis (equine herpesvirus-1 and -4 infections). In: Veterinary Medicine: A Textbook of the Diseases of Cattle, Horses, Sheep, Pigs, and Goats. 11th ed. Elsevier; 2017. p. 1040-1042.

- Gardiner DW, Lunn DP, Goehring LS, Chiang YW, Cook C, Osterrieder N, et al. Strain impact on equine herpesvirus type 1 (EHV-1) abortion models: viral loads in fetal and placental tissues and foals. Vaccine. 2012;30:6564-6572. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.08.046

- Gibson JS, Slater JD, Field HJ. The pathogenicity of Ab4p, the sequenced strain of equine herpesvirus-1, in specific pathogen-free foals. Virology. 1992;189:317-319. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/0042-6822(92)90707-V

- Gibson JS, Slater JD, Awan AR, Field HJ. Pathogenesis of equine herpesvirus-1 in specific pathogen-free foals: primary and secondary infections and reactivation. Arch Virol. 1992;123:351-366. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01317269

- Tearle JP, Smith KC, Boyle MS, Binns MM, Livesay GJ, Mumford JA. Replication of equid herpesvirus-1 (EHV-1) in the testes and epididymides of ponies and venereal shedding of infectious virus. J Comp Pathol. 1996;115:385-397. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/s0021-9975(96)80073-9

- Walter J, Balzer HJ, Seeh C, Fey K, Bleul U, Osterrieder N. Venereal shedding of equid herpesvirus-1 (EHV-1) in naturally infected stallions. J Vet Intern Med. 2012;26:1500-1504. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-1676.2012.00997.x

- Hebia-Fellah I, Léauté A, Fiéni F, Zientara S, Imbert-Marcille BM, Besse B, et al. Evaluation of the presence of equine viral herpesvirus 1 (EHV-1) and equine viral herpesvirus 4 (EHV-4) DNA in stallion semen using polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Theriogenology. 2009;71:1381-1389. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.theriogenology.2009.01.009

- Doll ER, McCollum WH, Bryans JT, Crowe ME. Effect of physical and chemical environment on the viability of equine rhinopneumonitis virus propagated in hamsters. Cornell Vet. 1959;49:75-81. Available from: https://scispace.com/papers/effect-of-physical-and-chemical-environment-on-the-viability-44sj6cy8mb

- Allen GP. Antemortem detection of latent infection with neuropathogenic strains of equine herpesvirus-1 in horses. Am J Vet Res. 2006;67:1401-1405. Available from: https://doi.org/10.2460/ajvr.67.8.1401

- Crowhurst FA, Dickinson G, Burrows R. An outbreak of paresis in mares and geldings associated with equid herpesvirus 1. Vet Rec. 1981;109:527-528. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6280366/

- Edington N, Bridges CG, Huckle A. Experimental reactivation of equid herpesvirus 1 (EHV-1) following the administration of corticosteroids. Equine Vet J. 1985;17:369-372. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2042-3306.1985.tb02524.x

- Wellington JE, Love DN, Whalley JM. Evidence for involvement of equine herpesvirus 1 glycoprotein B in cell-cell fusion. Arch Virol. 1996;141:167-175. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01718598

- Neubauer A, Braun B, Brandmüller C, Kaaden OR, Osterrieder N. Analysis of the contributions of the equine herpesvirus 1 glycoprotein gB homolog to virus entry and direct cell-to-cell spread. Virology. 1997;227:281-294. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1006/viro.1996.8336

- Csellner H, Walker C, Wellington JE, McLure LE, Love DN, Whalley JM. EHV-1 glycoprotein D (EHV-1 gD) is required for virus entry and cell-cell fusion, and an EHV-1 gD deletion mutant induces a protective immune response in mice. Arch Virol. 2000;145:2371-2385. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s007050070027

- Azab W, Osterrieder N. Glycoproteins D of equine herpesvirus type 1 (EHV-1) and EHV-4 determine cellular tropism independently of integrins. J Virol. 2012;86:2031-2044. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1128/jvi.06555-11

- Matsumura T, Kondo T, Sugita S, Damiani AM, O’Callaghan DJ, Imagawa H. An equine herpesvirus type 1 recombinant with a deletion in the gE and gI genes is avirulent in young horses. Virology. 1998;242:68-79. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1006/viro.1997.8984

- Bryant NA, Davis-Poynter N, Vanderplasschen A, Alcami A. Glycoprotein G isoforms from some alphaherpesviruses function as broad-spectrum chemokine binding proteins. EMBO J. 2003;22:833-846. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/emboj/cdg092

- Van de Walle GR, May ML, Sukhumavasi W, von Einem J, Osterrieder N. Herpesvirus chemokine-binding glycoprotein G (gG) efficiently inhibits neutrophil chemotaxis in vitro and in vivo. J Immunol. 2007;179:4161-4169. Available from: https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.179.6.4161

- Azab W, Zajic L, Osterrieder N. The role of glycoprotein H of equine herpesviruses 1 and 4 (EHV-1 and EHV-4) in cellular host range and integrin binding. Vet Res. 2012;43:61. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/1297-9716-43-61

- Neubauer A, Osterrieder N. Equine herpesvirus type 1 (EHV-1) glycoprotein K is required for efficient cell-to-cell spread and virus egress. Virology. 2004;329:18-32. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virol.2004.07.034

- Rudolph J, Osterrieder N. Equine herpesvirus type 1 devoid of gM and gp2 is severely impaired in virus egress but not direct cell-to-cell spread. Virology. 2002;293:356-367. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1006/viro.2001.1277

Article Alerts

Subscribe to our articles alerts and stay tuned.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Save to Mendeley

Save to Mendeley